Monday, January 14, 1946. Wartime and Post War foodstuffs.

Lex Anteinternet: So you're living in Wyoming (or the West in genera...So what about World War Two?

Lex Anteinternet: So you're living in Wyoming (or the West in genera...So what about World War Two?

Well our fathers fought the Second World WarSpent their weekends on the Jersey ShoreMet our mothers in the USOAsked them to danceDanced with them slowAnd we're living here in Allentown

Part of a post World War Two series of pamphlets for returning servicemen. Interesting for a vareity of reasons, including the sad one that this was apparently still an option, and now it is not.

The pamphlets bound in these two volumes represent a war-time experiment in the education of a citizen army. The story of the initiation and development of this joint enterprise of the Information and Education Division of the United States Army and the American Historical Association is familiar to those to whom these volumes go as an acknowledgment of their interest and cooperation. The files of the Historical Service Board to whom the Association transferred the execution of the program will ultimately be available to the historian. It is necessary here to recall only the outlines of the enterprise.

In August 1943 Colonel Francis T. Spaulding representing the Army under authority of his superior, General Frederick H. Osborn, sought out the Executive Secretary of the American Historical Association and laid before him the plan of a series of discussion pamphlets to be used in voluntary forums on personal and public questions that the soldiers wished to discuss. Colonel Spaulding urged the project as a public service which the American Historical Association with its reputation for scholarship and impartiality was preeminently fitted to perform. Mr. Ford indicated his interest and called a meeting of the Executive Committee of the Association on September 2 which heard General Osborn and Colonel Spaulding and approved the signing of a contract with the Army. It also authorized the appointment of a director and staff and of an advisory board of historians and other social scientists.

The advisory board became the Historical Service Board and functioned faithfully and conscientiously until the end of its task on December 31, 1945. The following served on the Board: Professor Shepard B. Clough, Columbia University; Professor Robert E. Cushman, Cornell University; Dr. Guy Stanton Ford, American Historical Association; President Dixon Ryan Fox, Union College (January 30, 1945) ; Dr. Waldo G. Leland, American Council of Learned Societies; Dr. Edwin G. Nourse, Brookings Institution; Professor J. Salwyn Schapiro, College of the City of New York; Professor Arthur M. Schlesinger, Harvard University; Professor Robert R. Wilson, Duke University; Dr. Donald Young, Social Science Research Council.

It was a matter of great good fortune that Dean Theodore C. Blegen of the Graduate School of the University of Minnesota accepted the directorship and was released for national service by the regents of his university. Under a less capable and energetic scholar and administrator the program might easily have failed of its purpose. Dean Blegen selected as his assistant director Mr. Thomas K. Ford, editorial writer on the St. Paul (Minnesota) Dispatch and Pioneer Press, as editor Miss Sarah A. Davidson, and as assistant editor Mrs. Selma P. Larson. When Dean Blegan returned to his university duties at the end of the first year he retained an active interest as a member of the Board and Mr. Thomas Ford assumed the direction of the project while the Executive Secretary of the Association, as Acting Director, kept in constant touch with both the staff of the Board and of the Information and Education Division of the War Department.

It was not all smooth sailing. Nor was the selection of topics and authors, the editing and checking of manuscripts an absolute guarantee of prompt printing and circulation. Patience and good will ultimately overcame even the most exasperating delays. Major Donald W. Goodrich and his successor Captain H. Donald Crawford served admirably as liason officers in the Education Branch. To Major Edward Evans, on whose shoulders fell responsibility for art editing and production, belongs great credit for the attractive appearance of the booklets.

No authors' names were attached to the pamphlets. It was so planned and sometimes a pamphlet was so thoroughly a joint project, to which the staff members contributed much, that authorship would have been hard to allocate. Fees paid to the authors were no full recompense for the effort expended. Men and women laid aside other tasks or labored many added hours in response to the call to put scholarship at the service of the citizen soldiery. In all forty-four pamphlets were printed even though the end of hostilities caught many projected pamphlets still on the ways. Anyone who considers the substance and approach of these pamphlets may well ask, Should the end of a war stop what might be an even greater service in peace?

Without assigning names to pamphlets it is fitting to close this brief memorandum with a list of those who as authors made major contributions to one or more pamphlets: Frank S. Adams, Carl W. Blegen, Blair Bolles, Phillips Bradley, Arthur H. Brayfield, Albert L. Burt, Ralph D. Casey, Dean A. Clark, Katharine G. Clark, Thomas C. Cochran, Merle Colbe, Kenneth Colegrove, Vera M. Dean, Everett E. Edwards, Mario Einaudi, Robert N. Farr, Millard C. Faught, Sheldon Glueck, Lewis Hanke, Richard H. Hart, Herbert Heaton, Dorothy C. Kahn, Felix M. Keesing, Grayson L. Kirk, Clifford Kirkpatrick, Joseph G. Knapp, Eleanor Lattimore, Robert D. Leigh, Arthur O. Lovejoy, William Miller, Horace T. Morse, Ralph O. Nafziger, Anthony Netboy, Catherine Porter, Henry Reining, Jr., Thorsten Sellin, Horace Taylor, Robert Ulich, Dixon Wecter, Ray B. Westerfield, Edmund G. Williamson, John B. Wolf, Robert L. Wolff, Winslow H. Case (art).

Will you please accept these volumes as a token of appreciation for services thus acknowledged by the American Historical Association, the Historical Service Board, and the soldiers who have testified to their interest in the pamphlets.

Colonel Spaulding presented the material which he had previously given to Mr. Ford in St. Paul:

It is a matter on which they have been working since he first became associated with the Army. He speaks today with the approval of General Osborne, director of Special Services Division, War Department, who is responsible for the off-duty time of the Army. Started at first under Bureau of Public Relations, then transferred to General Osborne. One of the needs the War Department has recognized since before Pearl Harbor is the desirability of orienting men in service to the problems attendant on the war. Orientation course has dealt pretty exclusively with the events of the war—the ten years background and the daily progress. The course has not gone into surrounding, domestic, or purely national problems dealing with the events of war. There was issued some time ago an order to commanding officers that one day a week there should be a discussion period for men under unit commander to raise any questions they have in mind and talk freely about the orientation course. This was to be in training camps and all over. Discussion periods have gone more or less well—mostly the latter. The officers in charge have been exclusively engaged in training program and they have not had an opportunity to put their minds to the discussion program.

A year ago last February, when Colonel Spaulding first went on the job, there was under consideration a proposal for the freer, broader discussion of events of the war. There was an experimental try out of discussion group techniques in one or two camps in this country to see how it went. They selected a camp on the Atlantic seaboard and the commanding officer grudgingly gave permission to go ahead. For reasons unexplained the experiment was not carried out. They experienced a good deal of opposition from commanding officers who felt themselves so burdened by the training job that they did not want to see the men go into discussion; some felt it unwise to allow men to indulge in controversial discussions in the camps.

Last fall Colonel Spaulding studied with interest the British program which they had tried to start in 1939 and which it took them until 1941 to get going. They met with the same kind of opposition the American efforts have been meeting with the commanding officers. It did not take until large bodies of well-trained troops were able to take their minds away from the military aspect and think in broader terms.

This group analyzed the situation again last fall and drew up two schemes or procedures. These were never put through because they were not entirely satisfactory for the War Department group. In December, as a result of investigations, a number of civilian organizations were getting out discussion materials along matters of pretty current interest (OWI and Foreign Policy Assn. two of these groups). Also in December they discovered that the Readers’ Digest (hereafter, R.D.) had begun the publication and free distribution of pamphlets for discussion of current problems. The Army group discussed with the R.D. people the possibility of their making an edition of that sort especially for troops. Proposed to reprint articles in the magazine printed for the troops. They were not expecting to limit it to the R.D.; the Army used the R.D. because that organization had discovered how to get at the greatest number of people in a way that interests them; they have skillfully developed the kind of appeal and kind of writing that reaches down to people who are normally not interested. It was something to try out in order to test the procedure. The result of the conversations with the R.D. people was one issue of Camp Talk, which was distributed to 25,000 men in four service commands (two, eight, nine, and one other).

The second service command a year ago last February (1942) proved a difficult place to find an experimental camp; in December seventeen camps in the second service command were conducting self-organized discussion groups.

Results of circulation of Camp Talk: Postal cards enclosed with the magazine brought forth double the response received at any previous time from civilians. One officer within three days after receiving Camp Talk requested 3,500 copies of the second issue instead of the 2,500 planned on (the second issue never came out for reasons undisclosed). Out of 1,000 letters there were only 12 that were unfavorable.

Enough Camp Talks were provided for every man in every unit group. They had four methods of distribution, one of which was putting them where every man could get them if he wanted a copy. They estimated that this issue reached about 60 per cent of the men—in terms of the abilities as you go down the scale. They found that even where there was not organized discussion there was a good deal of talk among groups of two or three. The interest ran high even among the men who did not talk about the magazine. They used a method of non-selective distribution in order to find out what groups it appealed to. They learned about the technique of doing the job.

Shortly after they made this experiment Drew Middleton’s article appeared (he wrote from North Africa). He said there was no interest among American troops in the discussion of serious problems; no program among American troops for the development of discussion; American soldiers immature and, on the whole, gave a pretty black picture of the political intelligence and interest among American soldiers in North Africa. An article in the last Saturday Evening Post takes exception to Middleton’s article. Particularly among men who have been in combat there is a very deep and serious concern about where we are going and what this all means.

The British Army, in terms of personnel to deal with the problem, is much better off than we are at the present time—educated officers and programs in operation for four-year period.

The Army does not regret the condemnatory publicity on the opposite side. The attitude of the regular Army officers is that this is unnecessary, and unreliable; they base their judgments on their recollections of the peace-time Army. Forty per cent of our Army are high school graduates; the average army schooling is the high tenth grade (in the Navy before taking draftees, 11th grade). Our men may be politically immature, but they are not stodgy. Eighteen to twenty per cent of the men in the Army have had college work; there is a notable number of college graduates among enlisted men. In many cases there is a very distinct difference between officers and the enlisted men—officers find two or three men, at least, in their companies who are better educated than they are.

Our Congress is extraordinarily sensitive to the discussion of problems which might affect votes. There seems to be less jitteriness in Parliament with respect to what Army men talk about. The Congress is on sound ground with respect to their hesitation in this business.

The Army’s job is to educate the men for military and naval pursuits; it is not the Army’s job to try to educate the military personnel with respect to civilian pursuits. In the long run it would be very bad for the military services to do that. What they want to do is see to it that there is an opportunity to get education along these lines—the information to be presented should be determined by the most competent people to be found and prepared by civilian groups. The initiative ought to come from a group not tinged with military. American troops in England found themselves in the position where they wanted material for their troops and sent over for any material or suggestions and the Army finds itself without any good material to distribute. They presented samples. They need to develop materials usable at the option of the commanding officers; material that would serve as a basis for letting men discuss—and learn by discussion—matters that are of current and legitimate interest not just to soldiers but also to civilians. They need to get all possible authenticity, and not military authenticity. The material should be presented in such a way that it will do as nearly as possible the kind of thing the R.D. does—reach down with serious material as effectively as the R.D. does. The material should be framed for discussion leaders in such a way as to help them most effectively in striking the level of interest and type of interest among the men.

The best way to arrive at a solution would be to ask an associated like the AHA to help them develop materials—or develop the material—for the Army. The Army would like to enter into a contract to develop discussion group materials around topics suggested by the Army from time to time—topics decided upon after sounding out the men. They would like the Association to establish a staff of professional people to assure the authenticity of the materials presented.

Topics to be considered: I. Our Allies; II. Foreign Affairs; III. National Affairs; IV. Personal and Community Affairs.

Farming was among the earliest of civilized man’s occupations, and it has been the main economic basis of every civilization down to fairly recent times. Among ancient peoples, the landowner was regarded, along with the warrior, as the most respected and honored of men.

Our own American civilization is grounded on the ideals of a simple agricultural society. Many of the Fathers of our country, such as Washington and Jefferson, were farmers and their outlook on life largely shaped the spirit of our Constitution and government.

Perhaps the first question which anyone who considers taking up farming as a career asks himself is: Do I like farming as a way of life?

According to its devotees, farming offers satisfactions not often found in other tasks. Secretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard, himself a farmer, told a meeting of the Future Farmers of America on October 10, 1944: “I like farming. It is a good life. After more than 30 years of it, I still would rather farm than do anything else. I envy you future farmers who have such great things ahead.”

About ten years ago, Dr. O. E. Baker, a long-time student of agriculture, addressed a rural youth conference at the University of Illinois on the advantages of farm life. Dr. Baker-who may be regarded as a spokesman for the school of farming enthusiasts -said, “I have a son now less than 5 years old, and I hope when he grows up that he will decide to be a farmer.” Dr. Baker’s reasons for wanting his son to be a farmer were:

Let us examine briefly each of these points.

As to the question of diet, Dr. Baker based his assertion on (1) a United States Department of Agriculture study, made in fairly prosperous times, of 2,400 farm families and (2) a study by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics of 12,000 workingmen’s families in cities. The farm families, it was found, were getting much more protein, calcium, phosphorous, and iron than was necessary for good nutrition. The city families, on the other hand, were getting barely enough protein and not enough calcium, phosphorous, and iron.

The farm folk ate much more meat, eggs, milk, and vegetables—which they often produced themselves—than did the city folk, who depended more on cereals. Of course, city families with large incomes get more adequate food than workingmen’s families, but many farm people, if they moved to town, would undoubtedly fall into the latter class.

Of course, there are farm families who do not get a rich and varied diet, even in prosperous times like the present. In some agricultural areas there are farmers who have no gardens and keep no livestock. Some do not have enough cash income to buy adequate, wholesome food.

It is often remarked that one sees many more old people in the country than in the city. Does this mean that rural people live longer, despite the poor sanitary facilities and the lack of doctors and hospitals?

According to a census study based on 1920 figures, a newborn city baby, if a boy, could expect to live, on the average, to the age of 52. If he was born on a farm, however, and stayed there, the chances are he would live to be from 56 to 60 years of age. For females, the expectation of life was 55 in cities and 60 to 62 on farms. In 1940 rural death rates were 10 per cent lower than urban.

These figures are not conclusive evidence, however, that the farmer lives in more healthful surroundings than does the average city man. Other surveys indicate that farm people are probably sick oftener than city dwellers. According to some authorities, a farmer is less likely than city folk to contract certain diseases, such as those of the circulatory, respiratory, and digestive systems. But he is more likely to contract diseases traceable to poor sanitation and inadequate medical care, such as typhoid, malaria, measles, whooping cough, influenza, and dysentery. As better sanitation and medical care are provided in rural areas, the farmer’s disadvantage with regard to such diseases is certain to decrease.

Whether working in the fields, orchard, or garden or taking care of livestock, farming involves many kinds of tasks and skills. In addition, a farmer usually has to keep his equipment in good shape; do repair jobs around the house, barn, and sheds; clear out brush and cut fuel wood; possibly keep drainage ditches open or mend roads; and do a hundred and one odd jobs.

Those who prefer work in the country to work in the city contrast these varied tasks with the monotonous job of the factory hand who performs the same operation at high speed, hour after hour and day after day; or with that of the white-collar worker, sitting at his desk all day long, often under artificial light and in a hot, stuffy room.

Industrial life, say the farming enthusiasts, is a relatively new experience for man. The modern type of factory and the crowded and grimy industrial city have only been in existence for about a century. It is true that a large portion of our population-and that of other industrial countries-has become adapted to the speedy tempo and inflexible routine. Some even enjoy it, but many do not and would flee from the city if they could.

It is true that nearly all of us feel deep kinship with nature—but the farmer lives with it. He is intimately connected with the cycle of life. Many envy him and long for a small plot of soil where they can at least plant and grow flowers and vegetables.

There is, of course, the old saying, “The farmer’s day is never done.” The chores on a farm are many and the monetary rewards often limited. But many farmers do not think of their occupation solely in terms of cash.

To till the earth, to plant seeds and watch them grow, to see the young shoots mature in the summer sun, and then to harvest the crop are, to many people, deep and rewarding pleasures. So is the intimate association with animals—cattle, horses or mules, chickens, pigs, or sheep—dumb creatures who serve man well but who must be cared for tenderly and patiently.

These and other rewards of farming often compensate for a meager cash income, lack of household comforts, and constant worry about drought, frost, flood, or other unfavorable turns of the weather which may damage crops or ruin fields.

Those who prefer the city to the country have their answers to these arguments. Factory and office work, they say, may be less healthy and more nerve racking than farming. Cities may be noisy and crowded compared with the quiet and serenity of country life. But an urban environment is more stimulating mentally. Its social life is richer. It offers more opportunities for entertainment-organized sports, movies, and in some of the larger cities, legitimate theaters, symphony orchestras, operas, ballets, lectures, museums, and the like.

The city enthusiasts like to quote from Robert Browning: “Had I but plenty of money, money enough and to spare, The house for me, no doubt, were a house in the city-square; Ah, such a life, such a life, as one leads at the window there!

“Something to see, by Bacchus, something to hear, at least! There, the whole day long, one’s life is a perfect feast.”

Some sociologists say that the farmer tends to have a happier home life than the city man.

As a rule, farming is a family enterprise. The husband, wife, and children divide the labor, each doing what his or her strength and ability permit. By such teamwork, the family is knit into a tight and harmonious unit.

Because they work together as well as live together, farm families are generally more stable than urban families. This assertion is borne out by 1930 census figures which show that 19 per cent of family groups in cities were broken as against 14.7 per cent in villages and only 8.1 per cent on farms. According to the farming enthusiasts, family life and all it stands for seem to be more appreciated in rural than in urban communities, where people in normal times do not stay at home so much and outside distractions make the members of some families almost strangers to each other.

In answer to this, the city enthusiasts say that some farmers have more children than they can suitably provide for, and that the reason farm families tend to be more stable than urban families is that they don’t know how to get away from each other.

Those who prefer city life often use as a final and supposedly clinching argument the fact that farming ordinarily brings a relatively small income in cash.

What farmers have earned in the past is no certain guide to the future, but it does throw some light on the matter. According to the farm census of 1940, more than half the nation’s 6 million farm families had gross incomes of less than $1,000. This figure includes both money derived from the sale of crops and the value of food produced on the farm for home use. One-third of the over 3 million farm families with less than $1,000 gross income had supplementary earnings, usually because one or more members worked off the farm part of the year. But two-thirds had no such extra income.

Of course, farmers have been better off in the past four years than in the census year of 1940. Still, the high incomes commonly earned in other types of business are relatively rare in agriculture, except for the small percentage of farmers who work several hundred acres, keep large dairy or ranch herds, run huge fruit farms, and the like.

Those who prefer country life answer this argument by saying that, though city people generally earn more than farmers, they have to spend more. The cost of living is higher in urban than in rural areas. Rent is more; food costs more; it is necessary to have more clothes; and miscellaneous expenses are unquestionably greater.

But, ask the proponents of farming, is there as much solid satisfaction in such expenditure? Isn’t much of it devoted to “keeping up with the Joneses”?

Some economists even assert that the average farmer accumulates more wealth in his lifetime than the average city resident and that hence the farmer’s real income is higher than the city man’s.

Thus the arguments go back and forth, arguments which have doubtless been heard since cities first arose and the attractions of urban existence began to draw folk away from quiet, simple, country haunts.

“More and more,” says Secretary of Agriculture Wickard, “agriculture is becoming an exact science. It is a never-ending science, with many angles that open up avenues leading in all directions. The successful farmer still needs to have a love of the land, and practical experience, and plenty of courage and determination; but in addition he now needs a thorough grounding in the science of his calling. In the future this will be even more true.”

To be successful, a farmer must know a great deal about his land and the products he plans to raise.

Every plant and animal is a complicated organism. He who wishes to succeed in the culture of wheat, rye, corn, tobacco, or cotton, for example, must be thoroughly familiar with the characteristics of the plant, its germination and growth, the diseases and blights to which it is susceptible, and the methods of controlling them.

The dairy farmer and rancher must be acquainted with the characteristics of his cattle; their feed requirements, their breeding habits, and their common illnesses. Likewise, fruit farming requires expert knowledge of tree growth as well as grafting, pruning, spraying, and fertilizing.

In addition to knowing things like these, a farmer should have a sense of business, be able to sell his product where and when it is most profitable, keep adequate records (so as to know where he stands financially), and, above all, plan his production to take advantage of the most favorable markets.

After carefully weighing the pros and cons of farming versus other occupations and deciding in favor of the former, you are ready to consider the questions: Shall I buy or rent a farm? Where shall I farm? What kind of farming shall I undertake?

A wise choice takes many factors into account. To begin with, you should not buy or rent a farm unless you have had real experience in farming. You are almost certainly doomed to disappointment and failure if you undertake so complex a business without some experience on a good farm, under the guidance of a man who is a successful farmer. If you have had no experience, you should start a farming career as a hired man. After that you may be in a position to manage your own farm.

Mary experienced farmers stress the desirability of starting in as a tenant rather than purchaser. It is unwise to plunge into farming as an owner-operator until you have tried yourself out and know whether you like farming as a business, whether you can make a success of it, and whether you have chosen the kind of farming and location you want.

The region selected should be familiar, if possible. It is also helpful to settle where your family is known.

The region should be one that has been developed for many years, or, if new land, is close to good farming areas. The kind of agriculture that pays best in the vicinity should be a guide in determining the kind of farming selected. For example, Wisconsin is a renowned dairy state, and a dairy farmer probably has a much better chance of success there than in an area where such farming is comparatively rare. Similarly, if you prefer poultry farming, a region known for successful commercial poultry farming should be chosen.

Do not select a type of farming that is unfamiliar to the region. The chances are that the soil or climate is unfavorable and that the odds are against success.

In selecting a farm don’t be guided solely by interested parties, such as a real-estate broker seeking a fee or a seller anxious to get rid of his property. One should inquire fully into the past record of the farm, its yields, operating expenses, profits, and so on. Advice can usually be freely obtained from such well-informed and disinterested sources as county agricultural agents. State extension services, agricultural colleges, or experimental stations, and the various farm organizations can help on broader questions.

Climate is a key factor in determining the kinds of crops that can be grown, crop yields, and the type of livestock that will thrive in the region. Some of the climatic factors to be considered are the amount and distribution of rainfall during the year, length of the growing season, severity of the winters, and the possibility of such natural hazards as drought, flood, hailstorms, windstorms, and the like.

Good soil is perhaps the most essential element in farming since it determines not only what can be grown but whether yields will be high or low.

The size of the farm is naturally a major consideration. Half the nation’s 6 million farms produce very little for sale—in fact, only about 10 per cent of the total commercial produce. Before the war, many of the small farms, especially in such areas as the southern Appalachians, had more manpower than was needed.

The size of farm which a family can handle is constantly increasing as more machinery comes into use. For example, a farmer using one horse can plant an average of 5.5 acres of row crops, such as potatoes or corn, in a ten-hour day; with two horses he can plant 11.5 acres; but with a two-row planter and a tractor, 17 acres; and with a four-row tractor outfit, 33 acres. With the help of a horse mower, a farmer can mow about 8.5 acres in a ten-hour clay; with a tractor he can mow about 20 acres a day.

There are other factors to consider in choosing a farm, such as, are good roads available to haul the produce to market? A farm on a dirt road may be snowbound in winter or inaccessible during wet weather, and the farmer will be unable to get his milk, eggs, fruit, vegetables, and other products to market before they spoil.

Finally, the community advantages should be considered. A farm is a home as well as a business. A neighborhood with good schools, active churches, and social organizations such as lodges and farmer’s clubs is likely to be a place where farmers are fairly successful. A region with poor schools and backward community organizations is apt to have poor and struggling farmers.

Farm ownership, in view of economic conditions, may be a speculative undertaking after the war.

For those who plan to buy, it is well to remember the general rule of business that the more money invested the larger is the income, and vice versa.

The price paid for land, buildings, and equipment, if buying a developed farm, is perhaps the key in determining whether the venture. will be a success. If bought at inflated prices, the carrying charges plus taxes might lead to failure in the end even if crop yields were high for a number of years. A sharp decline in prices from wartime levels would make it difficult to meet mortgage payments and loans, bringing a loss of the entire investment. Such was the unhappy fate of many farmers after the last war.

The amount of capital required to get started as a farm operator depends on the kind of farming. Broadly speaking, there are seven types of farming particularly suitable for family operation: truck, poultry, dairy, stock, cotton, wheat, and diversified farming.

Truck or vegetable farming does not take much land, but the relatively few acres must be rich. Usually they cost as much as a general farm several times as large. A truck farm may be most desirable near a town or city where the crops can be sold as soon as they are ready. Such a farm is a highly specialized business, but often quite profitable.

Poultry farming is one of the most common and successful types of farming near the urban centers of the United States. If you plan to sell eggs, wholesale, it will take from 1,500 to 2,000 hens to keep a family fully employed; if, re tail, only 1,000 to 1,500 hens will be necessary. It may take just as much labor, however, to manage the smaller as the larger flock.

Since the poultryman usually buys all or most of his feed, only enough land—perhaps 10 acres or more—is necessary to provide range for the birds. Investment in buildings and equipment—brooder houses, laying pens, perhaps an incubator—is rather high. The United States Department of Agriculture estimates that a poultry farm with 2,000 hens needs $2,500 to $3,000 for stock and an additional $1,000 to $1,500 for equipment. Feed and miscellaneous supplies alone will require $1,500 or more annually—an investment all told of $5,000 or more, exclusive of land and dwelling.

Dairying is one of the most dependable types of farming. A satisfactory setup for a family farm is fifteen to twenty cows and a minimum of 80 to 120 acres of good land for the production of pasture, hay, and other feed for the stock. The starting capital required in the North, outside of land and buildings, is from $4,500 to $6,000, plus about $650 to $1,300 annually for seed, feed, fertilizer, and so on.

Stock farming (not grazing) is found most extensively in parts of the Middle West. The typical farm of this kind in the years 1938—42 had 170 acres, sold 56 cattle and 77 hogs each year, and kept about 100 laying hens. Of the 170 acres, 70 were in pasture, 34 in corn, 29 in small grain, 22 in hay, 5 in soybeans, and 10 in rotation pasture and miscellaneous crops. Such a farm had 5 milch cows. About 80 per cent of its gross income came from the sale of livestock and livestock products. This kind of enterprise means a considerable investment in land, stock, and equipment. Operating expenses are also comparatively high.

Cotton farming usually offers less income and requires less capital. Apart from the land, an investment of $800 to $1,000, plus operating capital of $400 to $500 a year for fertilizer, seed, and the like, may be sufficient. A typical upland cotton farm for family operation has, as a minimum, from 80 to 120 acres. Of these 15 to 20 are in cotton; 20 to 25 in corn (to feed mules, cows, hogs, and chickens); 8 to 10 in soybeans, cowpeas, or lespedeza for hay; and the rest in pasture and woodland.

Cotton farming in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California is usually on a much larger scale.

Since the price of cotton, unless pegged, moves up and down rapidly, it is desirable to grow other cash crops, such as peanuts, for additional income, besides producing on the farm as much as possible of the feed for animals and food for the family.

Wheat farming takes a good deal of land. Many of the wheat farms of Kansas, the Dakotas, and eastern Montana run to 640 acres or more. The United States Department of Agriculture estimates that it takes $3,000 to $4,000 for tools and equipment to get started in wheat farming, plus $1,000 to $2,000 for stock to provide additional income and keep manpower occupied during the months the wheat crop is not growing.

Diversified farming usually involves a mixture of cash crops and livestock. Its chief advantages are: (1) the risk is reduced by not banking mainly on one money crop and (2) it spreads the working time of the family. There are many possible combinations in this type of farming, such as growing cotton, peanuts, tobacco, and other crops in the South or dairying, hog raising, and poultry farming in the North. The main consideration is to plant crops which the operator can take care of and sell. The required investment in diversified farming varies with the region and the size of the business.

Part-time farming. Many men who are not interested in full-time farming may wish to engage in subsistence or part-time farming. Of the 6 million farmers in the United States in 1940, about 800,000 were part-timers, spending a hundred days or more a year in other occupations. Such farmers may have only a garden or they may cultivate several acres, keep a few hogs, a cow or two, and several score chickens. The crops and livestock may supply the bulk of the family’s food and a small cash income besides, anywhere from $10 to several hundred a year.

Investment in a farm involves (1) the land, farmhouse, and other buildings; (2) machinery and equipment; and (3) livestock-and work animals.

Few farmers have enough money at the outset to buy a farm outright. Most of them have to get long-term loans to finance the bulk of the investment. Such loans can be obtained from farm-mortgage companies, life-insurance companies, federal land banks which are part of the Farm Credit Administration, and from the Farm Security Administration.

Any man who has served ninety days or more in the armed forces since September 16, 1940, and been discharged under conditions other than dishonorable or who is released because of a disability incurred in line of duty is eligible for the loan benefits of the GI Bill of Rights. Under the provisions of this law he may be entitled to a guaranty by the Veterans Administration of loans to be used to buy or improve land, buildings, livestock, equipment, or machinery for farming operations.

The Veterans Administration does not lend the money itself; it guarantees 50 per cent of such loans—up to a maximum guaranty of $2,000. The interest rate may not exceed 4 per cent and the loan itself must be payable in not more than twenty years. Loans are approved for guaranty by the Veterans Administration if it finds that “the ability and experience of the veteran, and the nature of the proposed farming operations to be conducted by him are such that there is a reasonable likelihood that such operations will be successful,” and furthermore that the purchase price “does not exceed the reasonable normal value.” Interest for the first year will be paid by the Veterans Administration.

A veteran who goes first to such a federal agency as the Farm Credit Administration or the Farm Security Administration for financial help in locating on a farm has two strings to his bow. After he has got one loan from such an agency, or one insured by it, he can also get a second loan guaranteed by the Veterans Administration under the GI Bill. The full amount, up to $2,000, of this secondary loan may be guaranteed. The secondary loan, however, may not exceed 20 per cent of the cost or purchase price.

In certain areas loans up to $12,000 are also available from the Farm Security Administration to tenants, sharecroppers, and farm laborers to buy farms of their own. Under the GI Bill these loans are available to qualified veterans even though they are not tenant farmers. They are repayable over a period of forty years, interest figured at 3 per cent. Farm Security Administration loans may also be obtained for five years at 5 per cent for operating purposes-to buy equipment and stock, repair or improve farmhouses and other buildings, or buy fences, soil-building materials, and other necessary items.

For those who plan to rent a farm, the chief considerations arc (1) the land must be suitable for the type of farming planned; (2) the buildings and equipment should be in a satisfactory condition; and (3) the lease should be fair.

There are four basic types of leases: (1) the cash lease, (2) crop-share lease, (3) crop-share cash lease, and (4) livestock-share lease.

The advantages of the first are that the tenant in many cases is free to manage the farm as he pleases, and as a long-time proposition he may pay less rent than under crop-sharing arrangements. The chief disadvantage is that the tenant agrees to pay a definite sum before he knows what his income will be.

The crop-sharing lease is usually workable only in strictly cash-crop farming. The tenant gets part of the returns. Where these are relatively high, as on many Northern farms in good years, it is a fairly satisfactory type of tenancy.

The system of leasing on the basis of paying a fixed sum in cash as well as sharing crops is found throughout the Corn Belt of the Middle West. The landlord, because he receives some payment for the use of the land, pasture, and buildings, is interested in keeping his farm in good condition. This works to the advantage of the tenant.

The livestock-sharing lease may turn out to be a happy arrangement. A common method provides for joint ownership of the basic herd, with tenant and landlord sharing expenses and returns. Thus both are interested in the success of the business and both contribute what they can in capital to keep the buildings and fields in good condition.

What is a fair rental? And how should it be paid?

Here too it is best to get impartial advice from local people. In some instances the county agricultural agent may offer an opinion. The customs and rates in the community should be a guide.

Good lands now rent for $6 to $10 an acre. It is noteworthy that tenancy is most common on the best lands, such as the farms of the Corn Belt and the plantations of the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta region.

Cash rents, like the price of land generally, have risen during the war. In the postwar period, land values may decline and farm prices drop suddenly. In this event, rents agreed to at the beginning of the year, although in line with commodity prices at that time, may be too high at the end of the crop year, when farm prices have dropped. To safeguard yourself, cash leases should, if possible, be put on a sliding scale. In other words, the rental payment should be adjusted to the average price for the year of the basic cash crops grown on the farm.

Most farms are rented on a year to year basis. In 1940 about 60 per cent of the tenant farmers of the United States had been on their farms only since the previous growing season.

The best arrangement, if things work out well the first year, is a longer term lease, with a clause inserted stipulating that if unforeseen circumstances arise the lease may be terminated at the end of any one year. In this event, due notice-perhaps several months-should be provided for.

All farm leases should contain definite arrangements for (1) keeping the farm and buildings in good condition; (2) the general plan of farming; (3) contributions by each party to operating expenses; (4) making repairs (generally the landlord provides the materials and the tenant the labor) ; (5) provision for replacing buildings destroyed by fire, storm, or other hazard; (6) responsibility for carrying out soil conservation programs; (7) how the lease is to be terminated in case of death; and (8) how disputes about running the farm or other matters should be settled.

The county agricultural agent or an agent of the Farm Security Administration can supply the prospective tenant with a standard lease form. He will also furnish advice on other agricultural

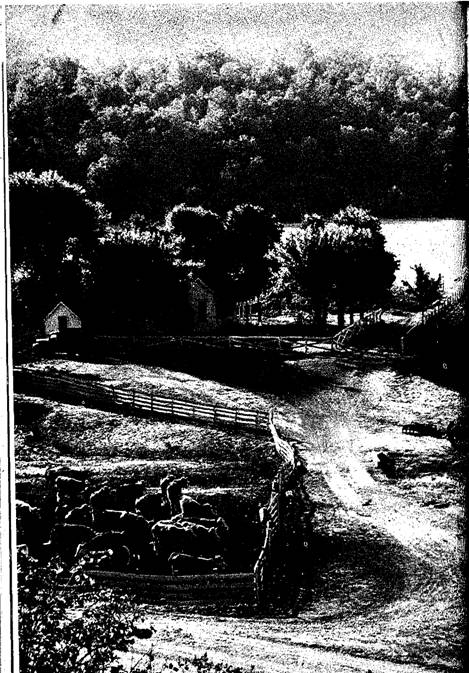

This is the life that city people often have in mind when they dream of farming. But farming is not a life of ease. It means long hours, hard work, little cash, and not much time for play.

An Iowa farmer and his wife figure up the balance for the year.

Here’s a man who gets his seed corn into the ground on time.

When the berries are ripe, women and children must help pick.

These Negro farmers learn the importance of soil conservation.

Sharecroppers work the land and divide the crop with the owner.

Dakota farm hand.

California olive grower.

Maine farmer.

Wyoming ranchers watch their stock being loaded for shipment to Midwest feed lots. There the cattle will be “finished,” that is, fattened up on corn before they go on to the packing house.

Here is a sea of wheat, part of a 6,000-acre ranch in the state of Washington. With such enormous fields, farm machinery not only can be, but has to be, used on a large scale to be efficient.

New Jersey truck farms grow tons of vegetables for New York City.

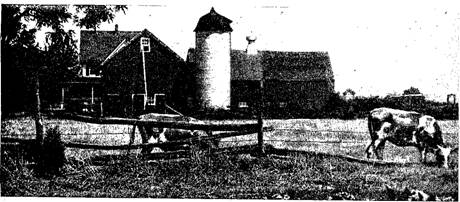

Milk of these Nebraska cows is sold through a cooperative dairy.

White Leghorns “line up” for chow on an Arizona chicken farm.

Acres and acres of cabbages to eat with corned you-know-what.

Cotton fresh off the bush.

Pigs is pigs-and bacon.

Avocados, like other orchard crops, need many hands at harvest.

Rich land, poor land, black loam and red clay, the far-rolling prairies and the Bullied hillsides, the wet lowlands and the fertile desert-these and many other kinds of land our farmers till. Much of their success depends on the quality of the land.

Winters are cold in New England and the northern tier of states.

Dry southwestern sunshine turns these spacious hills to brown.

Small farming affords independent living in the Middle South.

Big barns dominate the landscape of the Wisconsin dairy land.

Pastures in the South are green nearly the whole year round.

A California garden plot on a government resettlement project.

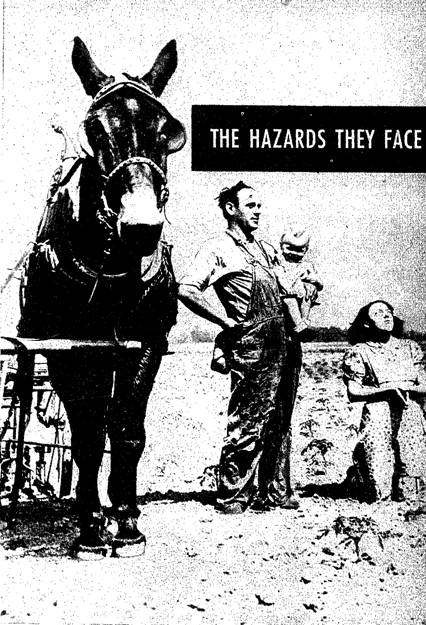

“Oh Lord, please send us rain!” Drought and dust and burned-out crops are but a few of the innumerable and unforeseeable hazards. Farming is a constant battle against the elements.

In case of fire about all you can do is to stand and watch it.

A twister in the sky means flattened crops and farm buildings.

Ever since Noah built his Ark, farmers have suffered in floods.

Good prices in one season may not last until the next season.

The grasshoppers have come to this cornfield, feasted, and gone.

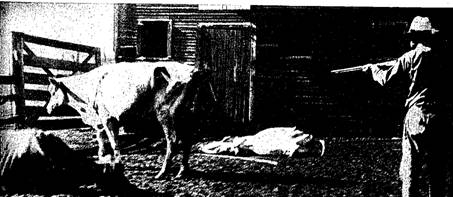

No rain, no forage, starving cattle, nothing to do but shoot.

Consolidated schools and high schools, to which farm children come by bus from miles around, are rapidly taking the place of the old-time, one-room, one-teacher country school building.

Everybody swings his partner at the Saturday night barn dance.

Where cattle is king the annual auctions are the big events.

In some communities the town meeting still functions as usual.

Everyone dresses in his or her store-bought clothes for church.

The Sunday school picnic is sure to draw a big and jolly crowd.

A wealth of agencies are ready to help those who go into farming. The county agent is usually the nearest, and he can be called upon as the occasion demands. The agricultural college and the agricultural experiment station of the state place scientific knowledge at the disposal of the farmer upon his application. Finally, the United States Department of Agriculture publishes a great variety of material on every conceivable phase of agriculture. Any farmer may obtain it merely for the asking.

What conditions will those who take up farming face after the war? What chance will a man have to make a satisfactory living from the soil?

These are debatable questions, and experts differ in their opinions. However, the past offers clues to the future. Those who plan on a farming career should know what another generation of farmers faced after the last war.

Since 1914 the American farmer has lived through a dramatic but short-lived period of prosperity, 1915 to 1919, followed by an era of hard times, 1920 to 1932, and then a gradual upswing which culminated in the boom. of World War 11.

The farm prosperity of World War 1, like that of industry, was due to enormous European orders, to rising purchasing power in the United States, and the need of supplying our own large armed forces.

Before World War 1, Great Britain, France, Belgium, and Italy depended heavily on other European countries, and on Australia, Argentina, the United States, and Canada for a considerable portion of their food staples. As the war disrupted these normal trade channels, they began to look more and more to us for their food imports, desperately needed to feed French and British civilians at home, as well as French and British armies and navies fighting on land and sea.

“Food Will Win the War!” was the slogan of the day. In response American farmers plowed up grasslands, pastures, and idle fields and planted them to wheat and corn. They raised and slaughtered more cattle and hogs; milked more cows, and produced more milk, butter, cheese, and eggs.

Demand for American farm products soon exceeded the supply. As a result, prices skyrocketed.

A few figures will tell the story perhaps better than many words. In the five years before 1914 American farmers averaged about 90 cents a bushel for their wheat. As Allied purchasing agents began bidding against one another and speculators jumped in to take advantage of the situation, the average farm price rose to more than $2 a bushel by 1918.

Lured by high prices and urged by the government, farmers planted more wheat. From an average of about 50 million acres in the years just before the war, wheat planting increased to a peak of 76 million acres in 1919. And the gross income of wheat farmers climbed steadily from around $500 million a year before the war to over $2 billion in 1919.

In 1914 corn was bringing an average of 70 cents a bushel at the farm. In 1919 the price was $1.50 a bushel. The prices of livestock and livestock products, of cotton and tobacco, jumped almost as fast.

All this made farming quite profitable, at least for the half of the nation’s farms that produced on a commercial scale. Thus, the net income of all farmers, after paying for the supplies required to produce their crops, rent, taxes, and interest on loans and mortgages, increased 120 per cent from 1914 to 1919. In the same period, the net income of the nonfarming population rose only 75 per cent.

This situation did not last long after the Armistice. In 1920 agricultural prosperity vanished and farmers began a long uphill battle to gain better incomes.

How did the sudden reversal of fortune come about? American agricultural prices-at least for some staples-arc geared to a world market. It is not alone what buyers in Kansas and the Dakotas offer for wheat that determines the price which our farmers normally get, but what buyers in England, Germany, France, and Italy deem it necessary to pay. The prices offered by local buyers in the wheat areas of the United States reflect the demand outside this country for the amounts in excess of that needed by our own people.

Similarly, the price of raw cotton and tobacco, unless pegged, is fixed substantially by the competition of world markets. It reflects what British and other foreign buyers are willing to pay, as well as what American purchasers offer.

Consequently, when there is a great export demand for farm products, prices are apt to be high. When overseas demand declines, as it did in 1920, prices are sure to drop.

In 1920, European agriculture was returning to. normal. Millions of men, discharged from the armies of the warring nations, came home to plant and harvest crops on fields scarred by trenches and shellholes. Also, prewar trade channels were being reopened and even former enemies; such as Great Britain and Germany, were doing business with each other.

American farmers had to compete again for European trade with the other great food-producing countries of the world. Then, too, Allied countries had expended the credits made available to them by our government and did not have the money to purchase the foodstuffs they needed. All these forces led to the collapse of demand. This in turn caused the collapse of farm prices.

The turning point came about the time the 1920 crops were reaching the market. Within a few months agricultural producers of every class were swept along under the avalanche of falling prices. And meanwhile surpluses piled up and granaries and warehouses were bulging with wheat and corn, tobacco and cotton, pork and other products.

There was a recession in industry, too, beginning in 1921 and lasting two years. The agricultural decline lasted much longer. How bad was the farm slump?

By 1921 farmers were getting only about 52 cents a bushel for corn-a drop of 60 per cent in two years; 19 cents a pound for cotton compared with 35 cents in 1919; and 19 cents a pound for tobacco compared with 31 cents in 1919. The price of wheat also tobogganed-by 1923 it was less than half the 1919 peak.

All through the 1920’s farmers generally were encountering hard times compared with other sections of the population. In other words, agriculture generally did not share in the prosperity of the 1923 to 1929 period. Many farmers, in fact, were caught in a “squeeze”—getting relatively low prices for what they produced and paying heavy fixed charges, such as taxes and interest, on loans and mortgages.

After the stock market crash of 1929 and the swift decline of industrial activity, the plight of a large portion of those who made their living from the soil grew steadily worse. The rapid increase of unemployment and loss of foreign trade, the melting away of the national income, all helped to bring the demand for farm products down to a record low.

Thousands of farmers went broke. Many others, who had bought their land at inflated wartime levels, could not meet the payments, on their mortgages and lost their farms. Still others lost their holdings because of heavy arrears in taxes.

It was difficult for many who managed to retain their farms to make ends meet with wheat selling, as in 1931 and 1932, at 38 or 39 cents a bushel (at the farm), corn at 31 or 32 cents a bushel, cotton at 6 or 7 cents a pound, and tobacco at 8 to 10 1/2 cents a pound.

Many formerly prosperous farmers had to become tenants or farm hands. For example, in 1935, over 40 per cent of the farms in the United States were being operated by tenants, compared with 25 per cent fifty years before.

Some operators and tenants were turned completely adrift, moving from one part of the country to another to earn a pitiful living, picking cotton in the South, “knocking” apples in Virginia or Maryland, working as harvest hands on the grain farms of the Middle West, or winding up as fruit pickers in the California valleys.

Many farmers had been literally blown off the soil by the fearful dust storms of 1934 and 1935. that swept over the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and the Texas Panhandle. Here years of overplowing and overcropping former pasture and grassland had left, the soil in a condition where wind and water could sweep it away. When the dust storms came, farming was impossible.

The roads were full in those days of impoverished rural families moving wearily across the country in their jalopies, sleeping in the open or in trailer camps night after night. Many could not afford even a wagon, and just walked from place to place, rolling their belongings in baby carriages or pushcarts. For these people there was only a pitiful hand-to-mouth existence.

More than a decade of agricultural decline left deep marks on the rural way of life. Many farmers who were able to retain their land had very little money to spend on clothes, other store goods, or recreation. Farm improvements were out of the question for many operators; barns, farmhouses, and other buildings were allowed to deteriorate and cars, trucks, tractors, and other equipment to wear out. A considerable proportion of American farm families went on relief.

The social consequences were equally deplorable. Boys and girls, growing up on the farm, could see no future there and migrated to the cities, where many of them joined the ranks of the unemployed. In some areas, rural schools and other social services had to be curtailed as tax collections declined. Country storekeepers watched their business dwindle away; and thousands of rural banks, loaded with farm paper that had greatly depreciated in value, closed their doors.

In 1933 the federal government stepped in to help the farmer. In the next five or six years a number of agricultural relief measures were enacted. Thus, farmers were paid by the government for limiting the amount of acreage put to the plow and for curtailing production of basic crops, such as wheat, cotton, tobacco, corn, and hogs. Also federal agencies purchased a large portion of each year’s production of some commodities, such as wheat, corn, meat, flour, wool, hides, and sugar. Some of the government holdings were distributed free of charge to people on relief.

The federal government helped farmers who were paying high interest rates on loans and mortgages by making available loans at low rates, thus safeguarding them against foreclosure. And finally, some of the very poorest farmers and tenants—as in the cotton growing areas of the South, and the cutover regions of the Great Lakes states—were moved at federal expense to better land and given a chance to start over again. Some were loaned money to buy equipment, livestock, seed, and fertilizer.

By these and other means the condition of American farmers generally was improved in the years 1933 to 1939. Farmers were enabled to get fairly good prices for certain of their products and they did not continue to lose their farms at the same rate as in the 1920’s.

On the night of September 1, 1939, Hitler sent his legions thundering over the Polish border. Two years later, with virtually all of Europe engulfed, the war spread to the Pacific as well. As before, our allies found increasing need for the products of our farms, forests, and factories, our mills and mines. As a result, the United States entered upon the greatest era of prosperity it has ever known. And farmers shared fully in it as agricultural prices soared to record levels and production rose by leaps and bounds. Let us see exactly what the war has done.

Great Britain, cut off from the food resources of Continental Europe, turned to us as in 1914–18 for more and more of her food imports. The Soviet Union, some of its fertile cropland, such as the Ukraine, occupied by the Nazis for almost three years, sought food from us to help sustain the Red armies and to eke out the scanty diet of its civilian population. We shipped huge amounts under lend-lease-2,144 million dollars’ worth of food to Great Britain and 915 million dollars’ worth to the Soviets in the period from March 11, 1941, to June 30, 1944. There is a basic distinction, however, between the foods sought by our Allies in 1914–18 and in the present war. In the last war, there was a demand for bulky foods. In this war; there has been emphasis on prepared foods (dehydrated eggs, canned fish, and the like) and on processed meats.

The slogan in this war has been “Food Is a Weapon of War—As Important as Guns and Ammunition!” In response American farmers have planted more acreage, especially to high-nutrient crops like soybeans and peanuts, raised more livestock, particularly hogs, and produced more dairy products—cheese, butter, and eggs needed by our allies. Despite a shortage of labor and machinery, but with the help of very favorable weather, 1942 agricultural production, including crops, livestock, and livestock products, rose 24 per cent and 1943 production 29 per cent above that of the average years 1935–39.

Will the present high prices and extraordinary demands for farm products continue after the war or will the balloon burst swiftly, as it did in 1920?

What do the experts think?

It is generally agreed that the two main requirements for a. healthy agriculture in the United States are: (1) full employment and high national income to provide people with the money to buy the bulk of our farm output at prices profitable to the producer and (2) a large volume of foreign trade—both imports and exports—which would take care of agricultural surpluses. The first without the second will not bring farm prosperity.

Thus, a United States Department of Agriculture report on “The Farmer and War,” issued in January 1944, says that “if improved farm returns are to continue after the war, ways will have to be found to keep industry producing for our needs in times of peace somewhat comparable to the way we produce ... in time of war, so that consumers of farm products retain their employment and can earn enough to buy the food and other things they need and want.”. This report urges a freer international trade and suggests that the United States buy enough foreign goods to permit other countries to obtain the exchange—the dollars—needed to purchase our agricultural products.

Marion Clawson, an economist of the United States Department of Agriculture, writing in the Antioch Review in the summer of 1944, says that after the war our capacity to produce farm commodities will be greatly increased. Farms will be more mechanized. Land now used to grow feed for work horses and mules will be released for the production of human food. Better methods of cultivation and plant breeding will increase the yields from the same acreage and often from the same amount of labor.

After every war plans have been made for settling veterans on the land. Frequently, and especially after World War I, these plans fell short of success. This time, it is urged, we ought not to make the same mistakes. As Dr. Raphael Zon, an eminent student of land-use problems, says, “There should be no helter-skelter settlement in remote regions away from existing social and recreational facilities. New land settlement should not be developed simply as a haven of refuge for the unemployed. . . Such settlements should be located on good land that has not been inflated in value, and the individual farms should be of sufficient size to provide a reasonably good income.”

It may be, as some students of the land problem declare, that farm acreage will have to be reduced after the war in order not to flood the market with surplus farm products. In the crop year 1944, some 354 million acres were in crops. Dr. Bushrod Allin of the United States Department of Agriculture estimates that after the war, if the national income stays at 150 billion dollars per year, overseas demand for American produce is sharply curtailed from wartime levels, and better farming methods and increased mechanization bring greater yields, 327 million crop acres will be sufficient to supply our own population.

Such a reduction would be difficult and painful. It would mean that thousands of farmers, especially those on poor land, would have to seek other ways of making a living, and some acreage now in crops would have to be put in pasture or allowed to revert to forest.

On the other hand, some students believe that, in order to meet the nutritional needs of all our people, considerable areas must be added to our present cropland, and that such acreage is still available. An expansion can be justified, however, only if the demand for agricultural products increases, and if people who cannot now afford proper diets have enough, income to buy more adequate food.

Whatever happens, it is clear that opportunities for new farmers after the war will depend in some measure on expansion of acreage in cultivation. If there is an actual over-all reduction, not many new farmers will be needed.

Regardless of the general situation, a certain number of developed farms will be offered for sale or rent each year. There are a good many over-age farmers on the farms of the United States at the present time. Many of them have done pretty well financially during the past few years and probably will want to retire soon after the war. If they do, they will make room for a good many young farmers. Judging by the record of the last five prewar years and other factors, it is estimated that from 250,000 to 350,000 good family-size farms may come on the market in the first five years after the war.

Also, desirable farms of various sizes will become available if and when new lands are developed. Their volume and location will depend on what kind of public work programs are undertaken, on the general condition of agriculture, and on the demand for additional farms. Some private capital, of course, will be forthcoming for these land developments.

There are millions of acres of dry lands which can be irrigated in the Western states and made available to farmers when projects now under construction or authorized are completed. Such lands, for example, are found in the Columbia River Basin in the state of Washington (where great expanses of sagebrush desert and abandoned farmlands can be reclaimed), in the central valley of California and in Arizona and the Intermountain states.

In the Columbia River Basin, types of farming which combine livestock and crop production seem to have the greatest promise. The government is authorized to buy large blocks of this land and subdivide it into family-size units for sale or lease.

The Bureau of Reclamation of the Department of the Interior estimates that from 2 to 5 million acres of newly reclaimed western land will become available within the next ten years. This would provide from 25,000 to 50,000 new farms. In addition, supplemental water will be provided for 5 million acres now inadequately irrigated.

Some additional acreage can be developed by draining the wooded lowlands along the Mississippi River in the states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Missouri, and the Coastal Plain of the South Atlantic states and the Gulf of Mexico. Such projects, however, are largely in the rather distant future and not many new farms can be expected in the next few years.

The Army and Navy have been using lands for airfields, bar racks, bombing ranges, proving grounds, and the like. The armed forces acquired altogether about 7 million acres during the defense and war period. Perhaps half of this area will be released. If so, as many as 10,000 farms and ranches of various sizes could be developed.

Finally, there is Alaska. The success of the agricultural colony planted in the Matanuska Valley during the depression has demonstrated—despite great handicaps—that farming can be made to pay in parts of this undeveloped territory. Some sections of the public domain—notably in the Tanana River Valley in the vicinity of Fairbanks, the Matanuska Valley, and on the Kenai Peninsula—which have good roads, are near to markets, and enjoy a favorable climate, can be successfully farmed.

Since Alaska now imports a large portion of its food supply from the States, homesteading offers a good chance of success to enterprising and hardy individuals. Anyone can obtain up to 160 acres of the public domain by cultivating the soil for at least three years. Under certain conditions veterans can shorten the period of residence and cultivation to as little as one year. A family intending to take up a homestead in Alaska should have sufficient funds to finance itself while putting the land on a productive basis, since much of it must first be cleared. For anyone seriously interested, the General Land Office, Department of the Interior, is the place to write for information.

Summing up the pros and cons, we find that many agricultural authorities believe that the outlook for the farmer is not bright. The problem of agricultural surpluses may arise in from two to four years after the war’s end—or when lend-lease and relief needs substantially drop off. These surpluses will probably be somewhat different from the surpluses that plagued us in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Instead of granaries loaded to the eaves with wheat, cotton, corn, and other nonperishables, we are likely to have surpluses of pork, butter, cheese, and so on, which cannot keep very long.

This fear of postwar farm surpluses is widespread. The War Food Administration, which procures food for the lend-lease program and for the armed forces, is planning—if Congress authorizes it—to get rid of its huge reserve stocks after the war by selling some in this country, distributing some to needy persons, and selling the rest overseas, probably at a loss. By the end of 1944, lend-lease shipments of food had dropped sharply. When the war in Europe ends, England, as a means of unifying the Empire, will tend to draw food supplies from its dominions and colonies instead of the United States; the Soviet Union will be able to supply its own needs for most agricultural products.

The future of agriculture, however, as of other industries and trade, is a question mark only because we cannot be sure what economic conditions will be like after the war. That farmers will be given considerable help by government action is a reasonable guess. Congress has declared that agricultural prices must be supported through federal subsidies, loans, crop purchases, and the like, for two years after the war, if farmers will elect to restrict production. Everything possible will doubtless be done to put a floor under farm prices and prevent their sudden collapse.

Taking all things into consideration, the future of farming in this country is closely tied up with general economic conditions. If industrial activity and foreign trade stay at high levels, farmers will surely share in the general prosperity.

Many American servicemen, wanting a change of occupation when once they are able to return to civilian life, are casting about for various types of opportunities-among them farming. They may think a farm offers a secure and independent living. Perhaps they believe a farm is a healthful and normal place to bring up children. It may be that they are motivated by a deep-rooted love of the soil typical of many Americans. In any case it seems reasonable to expect that many farmers now in uniform will return to the land and that they will be joined by many young men who were not farmers before the war.

These younger men particularly have many questions: What is the future of farming? Will a hard-working and intelligent farmer be able to make a living after the war? What kind of man does it take to make a successful farmer? Do farm families really lead a more healthful life than city families who have ready access to doctors and hospitals? What and where are the best farm opportunities? What does it cost to operate a farm? Your organizing a discussion based on this pamphlet will enable a good many men to do some realistic thinking on a possible postwar career.

In planning a discussion on farming as a postwar occupation, decide on a wording for your subject which you believe will bring. the men out to your meeting. Here are two such springboards for discussion:

As you study this pamphlet, other approaches to the general subject of farming will undoubtedly occur to you. One of these should fit into your discussion program better than any other.

Once you have decided on your main topic, you will want to prepare an outline of some sort to guide you in conducting the discussion and to enable you to cover as many important points as possible during the time at your disposal. Suppose, for example, you have chosen this subject: Should an ex-soldier take up farming? Your outline might list such important questions as:

Under each of these more important questions you would do well to list a number of other questions which tend to bring out specific minor points covered in the pamphlet. Many of the headings in the pamphlet phrase such questions; careful reading of the text will suggest others to you; still others are listed at the end of this guide.

An expert. It is a rare unit in which an experienced farmer cannot be found. Find such a man who is willing to answer questions and to help you make important points.

Discussion techniques. Either informal discussion or panel discussion will probably serve you best in handling this subject. Use the first if your group is smaller than 25 or 30; if it is larger, a panel of from 4 to 6 persons will develop more basic information and can serve as experts at the same time. Some of the panel members should be farmers and some should be city men.

Your best general guide to organizing and conducting forums and discussions is EM 1, GI Roundtable: Guide for Discussion Leaders. If you are interested in broadcasting discussions over radio or sound systems of the Armed Forces Radio Service, you should secure a copy of EM 90, GI Radio Roundtable. Other subjects already published in the GI Roundtable series are announced at the back of this pamphlet.

Reading. Provide copies of this pamphlet at key places (library, service club, or day rooms) where men who come to your meeting may read them. Men come not only for information, but for a chance to air their views. They will take more active part in discussion if their ideas have been stimulated by reading.

The United States Armed Forces Institute publishes a number of texts in agriculture. Two of these are related to a general discussion of farming: EM 800, What Is Farming? and EM 810, Managing a Farm. They may be procured from any information-education officer, from USAFI, Madison 3, Wisconsin, or from any USAFI Oversea Branch.

These additional titles are suggested fox supplementary reading if you have access to them or wish to procure them from the publishers. They are not approved nor officially supplied by the War Department. They have been selected because they give additional information and represent different points of view.

Many publications containing useful and authoritative information are available from the United, States Department of Agriculture, Washington 25, D. C. In addition, the Department is continually issuing new publications. It is suggested, therefore, that anyone writing to the Department should state the general nature of his interests and ask for publications relating thereto. Some of the following may prove interesting:

Getting Started in Farming. By Martin R. Cooper. Farmer’s Bulletin No. 1961 (1944).

Shall I Be a Farmer? By Paul V. Maris (1944).

Farmers in a Changing World. United States Department of Agriculture, Yearbook, 1940.

Farming As a Life Work. By O. E. Baker. Extension Service Circular 221 (1935).

About That Farm You’re Going to Buy. Farm Credit Administration Circular E-29 (1944).

Selecting and Financing a Farm. Farm Credit Administration Circular 14 (1942).

From the United States Department of the Interior, Washington 25, D. C., the following publications may be obtained: Alaska: Information Relative to the Disposal and Leasing of Public Lands in Alaska. Information Bulletin of General Land Office (1944).

Settlement of the Columbia Basin Reclamation Project. By Bureau of Reclamation (1944).

The following publications are also suggested:

Farm People and the Land after the War. By Murray R. Benedict. No. 28 of Planning Pamphlets, published by National Planning Association, 800 Twenty-first St., N. W., Washington, D. C. (1943).

Practical Farming for the South. By Benjamin F. Bullock. Published by University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, N. C. (1944).

Farm Primer: A Manual for the Beginner and Part-Time Farmer. By Walter M. Teller. Published by David McKay Co., 604 South Washington Square, Philadelphia, Pa. (1942).

Roots in the Earth: The Small Farmer Looks Ahead. By P. Alston Waring and Walter M. Teller. Published by Harper and Brothers, 49 East 33d St., New York 16, N, Y. (1943).