Sunday, December 21, 2025

Sunday, December 14, 2025

Tuesday, May 14, 2024

Blog Mirror: A bucket-list tour of Nebraska courthouses yields some elevator insights

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

Friday, March 25, 2022

Lex Anteinternet: Nebraska Ranchers to go into Meat Processing

Nebraska Ranchers to go into Meat Processing

I've written about how the State should sponsor something like this here:

Nebraska ranchers have a plan to contend with Big Beef and restore local economy

And they just hit the Wall Street Journal:

Cattle Ranchers Take Aim at Meatpackers’ Dominance

Nebraska cattlemen plan to build their own butchering plant to bypass America’s meat-processing giants, which they say underpay for livestock

I'd note that this might help Wyoming ranchers too.

Meat processing has become, over the years, one of the most concentrated industries in the U.S. I.e., the Sherman Anti Trust Act has apparently taken a vacation in regard to them, as there are hardly any owners. This actually became the topic of a Presidential statement relatively recently, albeit before the news became dominated by Vladimir Putin's desire to become the Czar. The President's statement was summarized on the Presidential blog:

Recent Data Show Dominant Meat Processing Companies Are Taking Advantage of Market Power to Raise Prices and Grow Profit Margins

By: Brian Deese, Sameera Fazili, and Bharat Ramamurti

The Biden Administration has been working at every level to address supply chain issues that are affecting prices. Many such issues are related to the pandemic—like changes in demand patterns, bottlenecks, or shutdowns. But for some price increases affecting Americans, there’s another culprit: dominant corporations in uncompetitive markets taking advantage of their market power to raise prices while increasing their own profit margins. Meat prices are a good example.

In September, we explained that meat prices are the biggest contributor to the rising cost of groceries, in part because just a few large corporations dominate meat processing. The November Consumer Price Index data released this morning demonstrates that meat prices are still the single largest contributor to the rising cost of food people consume at home. Beef, pork, and poultry price increases make up a quarter of the overall increase in food-at-home prices last month.

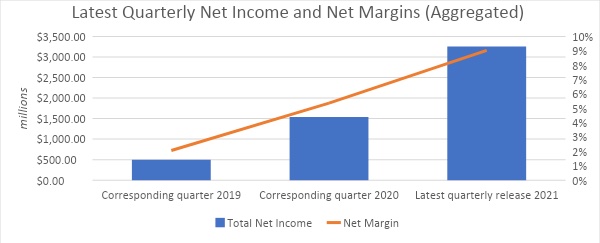

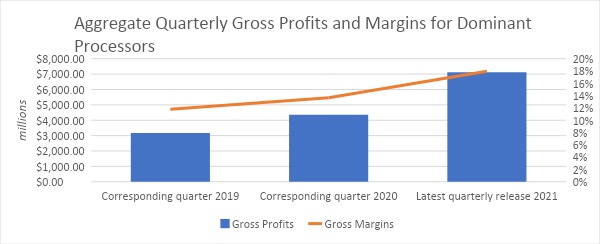

As we noted in September, just four large conglomerates control approximately 55-85% of the market for pork, beef, and poultry, and these middlemen were using their market power to increase prices and underpay farmers, while taking more and more for themselves. New data released in the last several weeks by four of the biggest meat-processing companies—Tyson, JBS, Marfrig, and Seaboard—show that this trend continues. (Other top processors are private companies that don’t report publicly on their profits, margins, or income.) According to these companies’ latest quarterly earnings statements, their gross profits have collectively increased by more than 120% since before the pandemic, and their net income has surged by 500%. They have also recently announced over a billion dollars in new dividends and stock buybacks, on top of the more than $3 billion they paid out to shareholders since the pandemic began.

Some claim that meat processors are forced to raise prices to the level they are now because of increasing input costs (e.g., things like the cost of labor or transportation), but their own earnings data and statements contradict that claim. Their profit margins—the amount of money they are making over and above their costs—have skyrocketed since the pandemic. Gross margins are up 50% and net margins are up over 300%. If rising input costs were driving rising meat prices, those profit margins would be roughly flat, because higher prices would be offset by the higher costs. Instead, we’re seeing the dominant meat processors use their market power to extract bigger and bigger profit margins for themselves. Businesses that face meaningful competition can’t do that, because they would lose business to a competitor that did not hike its margins.

As one large meat-processing firm noted to investors during its earnings call, their pricing actions “more than offset the higher COGS [cost of goods sold].” Comparing the fourth quarter of 2021 to the same quarter in 2020, that same firm increased the price of beef so much—by more than 35%—that they made record profits while actually selling less beef than before.

Here is the bottom line: the meat price increases we are seeing are not just the natural consequences of supply and demand in a free market—they are also the result of corporate decisions to take advantage of their market power in an uncompetitive market, to the detriment of consumers, farmers and ranchers, and our economy. They underscore why promoting competition is a core part of the Biden-Harris Administration’s economic agenda.

The Administration has already announced strong actions to crack down on illegal price fixing and enforce the antitrust laws robustly, investments of hundreds of millions of dollars to create more competition in meat-processing, over a billion dollars in relief to small businesses and agricultural workers hurt by COVID, and many other steps to ensure American families, farmers, and ranchers get a fairer shake. These are just a few of the actions we’re taking under our existing authorities.

Just yesterday, the Department of Agriculture announced that its loan guarantee program to invest in small meat processors and distributors is now open for business. The program will use $100 million in American Rescue Plan funding to leverage approximately $1 billion in lending capital through community and private sector lenders to expand meat and poultry processing capacity and finance other food supply chain infrastructure. This important investment in new private sector capacity will give producers more options, help bring competition to the meat-processing industry, and close vulnerabilities in the food supply chain revealed and exacerbated by the pandemic. It is in addition to the previously announced $500 million investment for expanded meat and poultry processing capacity.

In September, we also called for Congress to work together to enact greater transparency in cattle markets. We are encouraged to see that Senators have since announced new, additional efforts to work together to advance bipartisan legislation.

Together, these actions will support families, farmers, ranchers, and workers, and address the concentration in meat processing that makes it easier for dominant corporations to hike prices.

I have to say, if former President Trump had stated this, there'd be all sorts of rural cheers everywhere. In our current era of hyper partisanship, however, not much occurred.

Indeed, in an election year like this one, in which oil is up and down, and people were worried about the economy and the long term prospects for the state, surely this would be a heated issue that every candidate, particularly those running for the House of Representatives, would be focused on, right? We'd expect the candidate with rural roots to be discussing this, for one thing.

No, nobody is saying much.

Something definitely needs to be said.

And something needs to happen.

Prior related threads: