Questions hunters, fishermen, and public lands users need to ask political candidates. Addressing politicians in desperate times, part 2.

But these are not ordinary times in Wyoming, or anywhere else.

Most real outdoorsmen, and by that I mean the sort of outdoorsmen who have the world out look that those who post here do, not guys with excess cash who are petty princes like Eric Trump, would rather be hunting or fishing, or reading about hunting and fishing, than thinking about politics. But just like duck hunter (seriously) Leon Trotsky once stated; “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you,” and that applies to politics as well as war.

You might not be interested in politics, but politics is very interested in you.

And frankly, given the assault on everything hunters, fishermen, and the users of public lands hold dear, you don't really have the luxury, and that is what it is, of ignoring politics.

Nor do you have the luxury of ignoring your politicians.

Donald Trump was embarrassing his first term in office, but in his second unrestrained term in office, he and the Republican Party have been a disaster for outdoorsmen, nature, and the environment. Last year there was a diehard effort by Deseret Mike Lee to basically sell off massive parts of the public domain. That effort was supported by all three of Wyoming's Congressional delegation in spite of massive public opposition to it. This year a Freedom Caucus member, Rep. Wasserburger, is trying the same thing in the state with state lands. None of this should be any surprise as Freedom Caucuser Bob Ide, who campaigned on less government, more freedom, but who is a big landlord depending on the government to protect his property rights, sponsored an effort to grab the public lands the legislative session before that.

When put right to it, the Freedom Caucus hates government ownership of anything, and by extension, just flat out isn't really very concerned about the collective good on anything at all. They're an alien carpetbagging force in the country, but the sort of dimwitted views they have on nature and land are being expressed all across the country. Hunters, fishermen, farmers, ranchers, campers, hikers and other users of the land who had reflexively voted for one party or another based on some belief on what those parties held can absolutely no longer afford to do that.

Part of this is because politicians just flat out lie. People who naively thought that Donald Trump was a supporter of the Second Amendment, and therefore supported "gun rights" are finding out right now that he never believed any of that. Why would he? He's an old, fat, wealthy, New Yorker. It's not like you saw him at the range, now is it?

But chances are, you haven't seen California Chuck Gray there either, have you?

So, some questions that you, dear feral reader, really need to ask your politicians.

1. Do you have a hunting or fishing license right now, and if you do, can you pull it out of your wallet so we can see it?

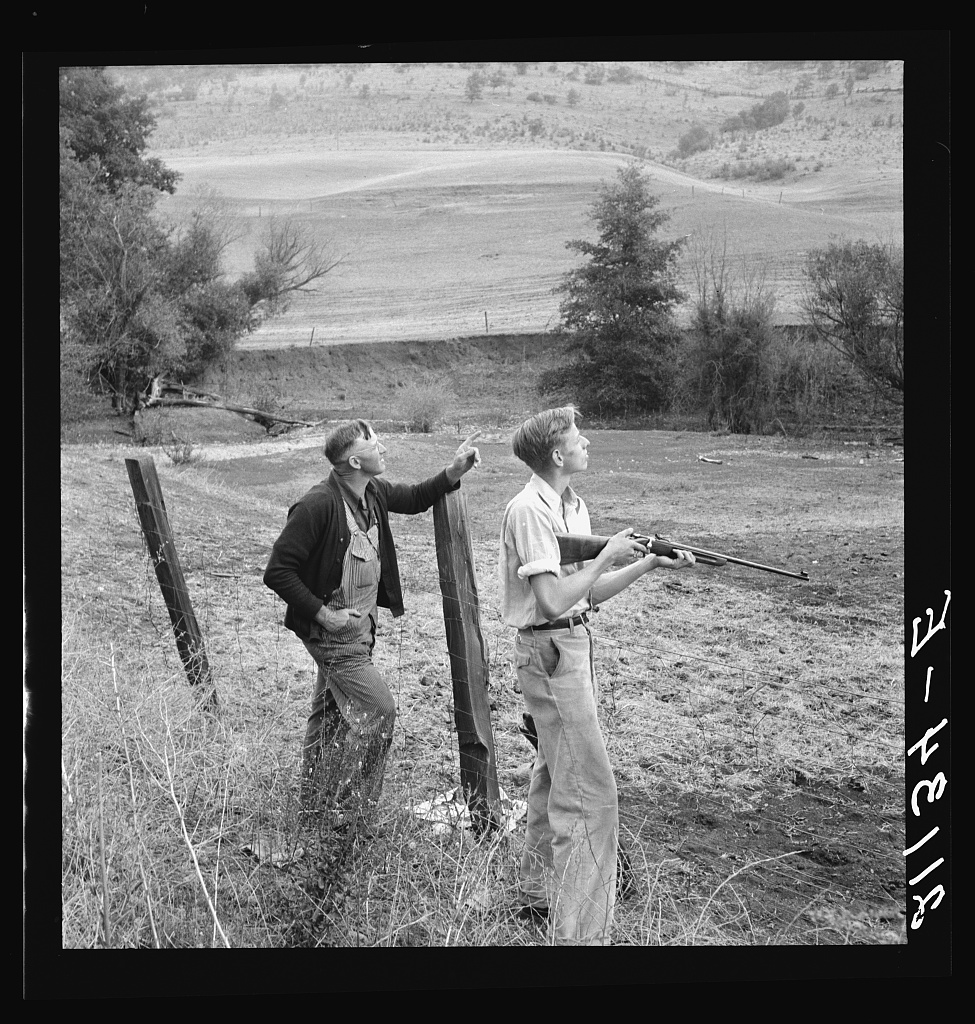

It used to be standard in Wyoming and Colorado, and I bet other Western states, to see a politician dragged out in front of a camera for an advertising campaign wearing brand new hunting clothing and carrying a shotgun (interestingly, never a rifle). It was a little fraud that we all participated in. We knew that the politicians would probably wet his pants if he had to fire the gun, but we took that as a symbol of support.

Don't.

Find out if they really share your values. Do they hunt, or fish? What's the proof?

And if they answer yes, find out what that means. Does it mean the politician goes sage grouse hunting every year or does it mean that he waddles on to a pheasant farm once a year to shoot some POW pheasants? Worse yet, does it mean that he went on a catered "hunt" in Texas with fat cats.

How often does he go, where does he go, does he use public land to hunt?

Same thing with fishing.

If he doesn't do either, and regularly, don't vote for him easily. Chances are he cares as much about hunting as Elon Musk does about marital fidelity.

2. Do you use public land for anything, and if so, what?

Nearly every feral person worth his salt uses public land. Does your Pol? And I mean for anything. Hunting, fishing, camping, running cattle, photography, running nude through the daisies. Anything.

And ask for proof.

If that proof is a photograph of a cleanly shaved pol with brand new clothing, it's proof he doesn't use it, or that she doesn't use it.

And if the answer is the typical "I love Yellowstone National Park", be very careful National Parks are great, but a lot of them aren't really very wild until you get off the beaten path. Going on an auto tour of Yellowstone and seeing all the geysers is great, but that's not proof of much. And quite a few of the "I support public lands" political class limits that support to parks. Everything is fair game for development in their view.

3. Do you shoot?

I don't expect every outdoor users to be a shooter, although in the West, if you are a user of wildlands and don't have a gun, you are a complete and utter fool. Having said that, I'll be frank that I have known fishermen who had one gun, probably a revolver, that they carried in some places. They probably went years between shooting it. I don't regard owning a gun as a precursor to all feral uses of land, particularly by people who don't hunt, but who do fish, or camp, or hike (but if you do any of these things, please get a handgun and learn how to use it).

A lot of people in the West vote for pols based solely on "I support the Second Amendment type statements". Lots of people allowed themselves to be duped into voting for Donald Trump that way, although we never believed his claims to be a Second Amendment supporter. We're sorry that we were so right. Anyhow, ask them if they have a gun and if they shoot.

No matter what they really believe, they're going to say yes.

I'll note I've seen this question asked just once, and when I did the female candidate, a native Wyomingite with a rural background, went on to qualify that she was just familiar with .22s. Okay, that's an honest answer.

She was, I'd note, a Democrat.

You do need to follow up on the question.

Right now, if you asked this question of Chuck Gray or John Barrasso, they'd both undoubtedly say yes. I don't know if either of them owns a firearm, but my guess is that if they do they own it in the way of people who have bought or been given a handgun that's gone in a drawer, and that's where it stays. Ask for proof. What do they own, where do they shoot, how often, and are there photos. And not photos from a gun show, like Reid Rasner posted the other day.

Take them to the range and have them shoot a box of .375 H&H. If they run to the SUV crying, they're out.

If they can't back this stuff up, I'd assume they really don't care about the Second Amendment. There are people who don't shoot at all who do care about the Second Amendment, but they're are rare as people who are interested in stock cars but don't follow NASCAR (this would describe me). Not too many.

4. Do they believe in man made climate change?

This gets to the land ethic. Educated people, and most politicians, are educated who say no really don't give a rats ass about the planet or they're engaging in diehard self delusion. They're comfortable with everything being destroyed as long as they're dead before it happens or they just can't face the hard task of addressing, correcting, and reversing it. They're not worth voting for.

5. Do they have a land ethic?

I've known a lot of people who have a very strong land ethic. Absolutely none of them didn't make use of wilderness in some ways.

That's a big clue.

Anyhow, more than anything else, do they have a land ethic? That is;

A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.

Aldo Leopold.

Do they support that?

A huge pile of Western politicians really don't. Some, however, who would surprise you do. This is a hard question to really explore, because an existential question isn't necessarily easy to question on. In a collegiate debate, you'd just state the proposition and ask if they agreed, or didn't and follow up with examples. That may be the best way to do it.

Nobody should vote for a politician who doesn't support the Land Ethic.

Last edition: