Contrary to our natures

When this blog was started several years ago, the purpose of it was to explore historical topics, often the routine day to day type stuff, from the period of roughly a century ago. It started off as a means of researching things, for a guy too busy to really research, for a historical novel.

It didn't start off as a general commentary on the world type of deal, nor did it start off as a "self help" type of blog either. Over time, however, the switch to this blog for commentary, away from the blog that generally hosts photographs, has caused a huge expansion here of commentary of all types, including in this category and, frankly, in every other.

The pondering professor of our Laws of History thread.

Readers of this blog (of which there are extraordinarily few) know that I've made a series of comments in the "career" category recently that touch on lawyers and mental health. They also know that I was working on a case (actually, two cases) in which an opposing lawyer, without warning or indication, killed himself. That's bothered me a great deal thereafter. It isn't as if we could have done anything, but that it occurred bothers me. And, as noted in the synchronicity threads, I've been reading a lot of comments in lawyer related journals and blogs on this topic as well. Perhaps they were always there and I hadn't bothered taking note of them, or perhaps that's synchronicity again.

In that category, I stumbled upon a piece written by a fellow who runs a very well liked blog, and who is a lawyer, but whom has never practiced. I very rarely check that blog, The Art of Manliness, but it's entertaining to read (or probably aggravating to read for some) and I was spending some early morning time in a hotel room waiting for a deposition to start and stopped in there for the first time in eons. Sure enough, there's an article by a lawyer on the topic of mental health. Specifically, there was an article on depression, which is the same thing that a lot of these lawyer journals are writing on. Having somewhat read some of the others, and being surprised to find this one, I read it. Turns out there's an entire series of them and I didn't read them all, but in the one I did read, I was struck by this quote:

If depression is partly caused by a mismatch between how our bodies and minds got used to living for thousands of years, and how we now live in the modern world, then a fundamental step in closing this gap isn’t just moving our bodies, but getting those bodies outside.

The "office" your DNA views as suitable. . . and suitable alone.

Indeed, I think a drove of current social and psychological ills, not just depression by any means, stem from the fact that we've built a massively artificial world that most of us don't really like living in. It's a true paradox, as I think that same effort lies at a simple root, the human desire to be free from true want. I.e., starvation. Fear of starvation lead us to farming to hedge against it, and that lead to civilization. Paradoxically, the more we strive for "an easy life", the further we take ourselves away from our origins, which is really where we still dwell, deep in our minds.

Okay, at this point I'm trailing into true esoteric philosophy and into psychology, but I think I may be more qualified than many to do just that. Indeed, I was an adherent of the field of evolutionary biology long before that field came to be called that, and my background may explain why. So just a tad on that.

Some background

With my father, at the fish hatchery, as a little boy.

When I was growing up, I was basically outdoors all the time, and I came from a very "outdoorsy" group of people. And in the Western sense. People who hunted and fished, garden and who were close to agriculture by heritage. They were also all well educated. There was no real separation in any one aspect of our lives. Life, play, church, were all one thing, much as I wrote about conceptually the other day.

When I went to go to college, post high school, I really didn't know what I wanted to do and decided on being a game warden, which reflects my views at the time, and shows my mindset in some ways now, set on rural topics as it is. However, my father worried about that and gently suggested that career openings in that field were pretty limited. He rarely gave any advice of that type, so I heeded his suggestion (showing I guess how much I respected his advice), and majored in geology, and outdoor field.

As a geology student, we studied the natural world, but the whole natural world back into vast antiquity. Part of that was studying the fossil record and the adaptive nature of species over vast time. It was fascinating. But having a polymath personality, I also took a lot of classes in everything else, and when I completed my degree at the University of Wyoming, I was only a few credits away from a degree in history as well.

Trilobites on display in a store window in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Now extinct, trilobites occurred in a large number of species and, a this fossil bed demonstrates, there were a lot of them.

That start on an accidental history degree lead me ultimately to a law degree, as it was one of my Casper College professors, Jon Brady, who first suggested it to me. I later learned that another lawyer colleague of mine ended up a lawyer via a suggestion from the same professor. Brady was a lawyer, but he was teaching as a history professor. I know he'd practiced as a Navy JAG officer, but I don't know if he otherwise did. If lawyer/history professor seems odd, one of the principal history professors at the University of Wyoming today is a lawyer as well, and the archivist at Casper College is a lawyer. I totally disagree with the law school suggestion that "you can do a lot with a law degree" other than practice law, but these gentlemen's careers would suggest otherwise.

Anyhow, at the time the suggestion was made I had little actual thought of entering law school and actually was somewhat bewildered by the suggestion. I was a geology student and I was having the time of my life. I was always done with school by late afternoon, and had plenty of time to hunt during the hunting season nearly every day, which is exactly what I did. By 1983, however, the bloom was coming off the petroleum industry's rose and it was becoming increasingly obvious that finding employment was going to be difficult. Given that, the suggestion of a career in the law began to be something I took somewhat more seriously. By the time I graduated from UW in 1986, a full blown oilfield depression was going on and the law appeared to be a more promising option than going on to an advance degree in geology. I did ponder trying to switch to wildlife management at that point, but it appeared to be a bad bet at that stage.

Casper College Geomorphology Class, 1983. Odd to think of, but in those days, in the summer, I wore t-shirts. I hardly ever do that now when out in the sticks. This photos was taken in the badlands of South Dakota.

Casper College Geomorphology Class, 1983. Odd to think of, but in those days, in the summer, I wore t-shirts. I hardly ever do that now when out in the sticks. This photos was taken in the badlands of South Dakota.

It's not impossible

Now, I know that some will read this and think that it's all impossible for where they are, but truth be known it's more possible in some ways now than it has been for city dwellers, save for those with means, for many years. Certainly in the densely packed tenements of the early 19th Century getting out to look at anything at all was pretty darned difficult.

Most cities now at least incorporate some green space. A river walk, etc. And most have some opportunities for things that at least replicate real outdoor sports, and I mean the real outdoor activities, not things like sitting around in a big stadium watching a big team. That's not an outdoor activity but a different type of activity (that I'm not criticizing). We owe it to ourselves.

Now, clearly, some of what is suggested here is short term, and some long. And this is undoubtedly the most radical post I've ever posted here. It won't apply equally to everyone. The more means a person has, if they're a city dweller, the easier for it is for them to get out. And the more destructive they can be when doing so, as an irony of the active person with means is that the mere presence of their wealth in an activity starts to make it less possible for everyone else. But for most of us we can get out some at least, and should.

I'm not suggesting here that people should abandon their jobs in the cities and move into a commune. Indeed, I wouldn't suggest that as that doesn't square with what I"m actually addressing here at all. But I am suggesting that we ought to think about what we're going, and it doesn't appear we are. We just charge on as if everything must work out this way, which is choosing to let events choose for us, or perhaps letting the few choose for the many. Part of that may be rethinkiing the way we think about careers. We all know it, but at the end of the day having made yourself rich by way of that nomadic career won't add significantly, if at all, to your lifespan and you'll go on to your eternal reward the same as everyone else, and sooner or later will be part of the collective forgotten mass. Having been a "success" at business will not buy you a second life to enjoy.

None of this is to say that if you have chosen that high dollar career and love it, that you are wrong. Nor is this to say that you must become a Granola. But, given the degree to which we seem to have a modern society we don't quite fit, perhaps we ought to start trying to fit a bit more into who we are, if we have the get up and go to do it, and perhaps we ought to consider that a bit more in our overall societal plans, assuming that there even are any.

Casper College Geomorphology Class, 1983. Odd to think of, but in those days, in the summer, I wore t-shirts. I hardly ever do that now when out in the sticks. This photos was taken in the badlands of South Dakota.

Casper College Geomorphology Class, 1983. Odd to think of, but in those days, in the summer, I wore t-shirts. I hardly ever do that now when out in the sticks. This photos was taken in the badlands of South Dakota.So what does that have to do with anything?

Well, like more than one lawyer I actually know, what that means is that I started out with an outdoor career with outdoor interests combined with an academic study of the same, and then switched to a career which, at least according to Jon Brady, favored "analytical thinking" (which he thought I had, and which is the reason he mentioned the possibility to me). And then there's the interest in nature and history to add to it.

Our artificial environment

Our artificial environment

So, as part of all of that, I've watched people and animals in the natural and the unnatural environment. And I don't really think that most people do the unnatural environment all that well. In other words, I know why the caged tiger paces.

People who live with and around nature are flat out different than those who do not. There's no real getting around it. People who live outdoors and around nature, and by that I mean real nature, not the kind of nature that some guy who gets out once a year with a full supply of the latest products from REI thinks he experiences, are different. They are happier and healthier. Generally they seem to have a much more balanced approach to big topics, including the Divine, life and death. They don't spend a lot of time with the latest pseudo philosophical quackery. You won't find vegans out there. You also won't find men who are as thin as pipe rails sporting haircuts that suggest they want to be little girls. Nor will you find, for that matter, real thugs.

You won't find a lot of people who are down, either.

Indeed the blog author noted above noted that, and quotes from Jack London, the famous author, to the effect and then goes on to conclude:

Truth be known, we've lived in the world we've crated for only a very brief time. All peoples, even "civilized people", lived very close to a nature for a very long time. We can take, as people often do, the example of hunter gatherers, which all of us were at one time, but even as that evolved in to agricultural communities, for a very long time, people were very "outdoors" even when indoors.

If depression is partly caused by a mismatch between how our bodies and minds got used to living for thousands of years, and how we now live in the modern world, then a fundamental step in closing this gap isn’t just moving our bodies, but getting those bodies outside.I think he's correct there. And to take it one step further, I think the degree to which people retain a desire to be closer to nature reflects itself back in so many ways we can barely appreciate it.

Truth be known, we've lived in the world we've crated for only a very brief time. All peoples, even "civilized people", lived very close to a nature for a very long time. We can take, as people often do, the example of hunter gatherers, which all of us were at one time, but even as that evolved in to agricultural communities, for a very long time, people were very "outdoors" even when indoors.

Ruin at Bandalier National Monument. The culture that built these dwellings still lives nearby, in one of the various pueblos of New Mexico. These people were living in stone buildings and growing corn, but they were pretty clearly close to nature, unlike the many urbanites today who live in brick buildings in a society that depends on corn, but where few actually grow it. The modern pueblos continue to live in their own communities, sometimes baffling European Americans. I've heard it declared more than once that "some have university educations but they still go back to the reservation."

Even in our own culture, those who lived rural lives were very much part of the life of the greater nation as a whole, than they are now. Now most people probably don't know a farmer or a rancher, and have no real idea of what rural life consists of. Only a few decades back this was not the case. Indeed, if a person reads obituaries, which are of course miniature biographies of a person, you'll find that for people in their 80s or so, many, many, had rural origins, and it's common to read something like "Bob was born on his families' farm in Haystack County and graduated from Haystack High School in 1945. He went to college and after graduating from high school worked on the farm for a time before . . . ."

Louisiana farmer, 1940s. Part of the community, not apart from it.

Now, however this is rarely the case. Indeed, we can only imagine how unimaginably dull future obits will be, for the generation entering the work force now. "Bob's parents met at their employer Giant Dull Corp where they worked in the cubicle farm. Bob graduated from Public School No 117 and went to college majoring in Obsolete Computers, where upon he obtained a job at Even Bigger Dull Corp. . . "

No wonder things seem to be somewhat messed up with many people.

Indeed, people instinctively know that, and they often try to compensate for it one way or another. Some, no matter how urban they are, resist the trend and continue to participate in the things people are evolved to do. They'll hunt, they fish, and they garden. They get out on the trails and in the woods and they participate in nature in spite of it all.

Others try to create little imaginary natures in their urban walls. I can't recount how many steel and glass buildings I've been in that have framed paintings or photographs of highly rural scenes. Many offices seem to be screaming out for the 19th Century farm scape in their office decor. It's bizarre. A building may be located on 16th Street in Denver, but inside, it's 1845 in New Hampshire. That says a lot about what people actually value.

Others, however, sink into illness, including depression. Unable to really fully adjust to an environment that equates with the zoo for the tiger, they become despondent. Indeed, they're sort of like the gorilla at the zoo, that spends all day pushing a car tire while looking bored and upset. No wonder. People just aren't meant to live that way.

Others yet will do what people have always done when confronted with a personal inability to live according to the dictates of nature, they rebel against it. From time immemorial people have done this, and created philosophies and ideas that hate the idea of people itself and try to create a new world from their despair. Vegans, radical vegetarians, animal rights, etc., or any other variety of Neo Pagans fit this mold. Men who starve themselves and adopt girly haircuts and and wear tight tight jeans so as to look as feminine as possible, and thereby react against their own impulses. The list goes on and on. And it will get worse as we continue to hurl towards more and more of this.

But we really need not do so. So why are we?

"It's inevitable". No it isn't. Nothing is, except our own ends. We are going this way as it suits some, and the ones it principally suits are those who hold the highest economic cards in this system, and don't therefore live in the cubicle farm themselves. We don't have to do anything of this sort, we just are, as we believe that we have to, or that we haven't thought it out.

So, what can we do

First of all, we ought to acknowledge our natures and quit attempting to suppress them . Suppressing them just makes us miserable and or somewhat odd. To heck with that.

The ills of careerism.

Careerism, the concept that the end all be all of a person's existence is their career, has been around for a long time, but as the majority demographic has moved from farming and labor to white collar and service jobs, it's become much worse. At some point, and I'd say some point post 1945, the concept of "career" became incredibly dominant. In the 1970s, when feminism was in high swing, it received an additional massive boost as women were sold on careerism.

How people view their work is a somewhat difficult topic to address in part because everyone views their work as they view it. And not all demographics in a society view work the same way. But there is sort of a majority society wide view that predominates.

In our society, and for a very long time, there's been a very strong societal model which holds that the key to self worth is a career. Students, starting at the junior high level, are taught that in order to be happy in the future they need to go to a "good university" so they can obtain an education which leads to "a high paying career". For decades the classic careers were "doctor and lawyer", and you still hear some of that, but the bloom may be off the rose a bit with the career of lawyer, frankly, in which case it's really retuning to its American historical norm.

Anyhow, this had driven a section of the American demographic towards a view that economics and careers matter more than anything else. More than family, more than location, more than anything. People leave their homes upon graduating from high school to pursue that brass ring in education. They go on to graduate schools from there, and then they engage in a lifetime of slow nomadic behavior, dumping town after town for their career, and in the process certainly dumping their friends in those towns, and quite often their family at home or even their immediate families.

The payoff for that is money, but that's it. Nothing else.

The downside is that these careerist nomads abandon a close connection with anything else. They aren't close to the localities of their birth, they aren't close to a state they call "home" and they grow distant from the people they were once closest too.

What's that have to do with this topic?

Well, quite a lot.

People who do not know, in the strongest sense of that word know, anyone or anyplace come to be internal exiles, and that's not good. Having no close connection to anyone place they become only concerned with the economic advantage that place holds for them. When they move into a place they can often be downright destructive at that, seeking the newest and the biggest in keeping with their career status, which often times was agricultural or wild land just recently. And not being in anyone place long enough to know it, they never get out into it.

That's not all of course. Vagabonds without attachment, they severe themselves from the human connection that forms part of our instinctual sense of place. We were meant to be part of a community, and those who have lived a long time in a place know that they'll be incorporated into that community even against their expressed desires. In a stable society, money matters, but so does community and relationship. For those with no real community, only money ends up mattering.

There's something really sad about this entire situation, and its easy to observe. There are now at least two entire generations of careerist who have gone through their lives this way, retiring in the end in a "retirement community" that's also new to them. At that stage, they often seek to rebuild lives connected to the community they are then in, but what sort of community is that? One probably made up of people their own age and much like themselves. Not really a good situation.

Now, am I saying don't have a career? No, I'm not. But I am saying that the argument that you need to base your career decisions on what society deems to be a "good job" with a "good income" is basing it on a pretty thin argument. At the end of the day, you remain that Cro Magnon really, whose sense of place and well being weren't based on money, but on nature and a place in the tribe. Deep down, that's really still who you are. If you sense a unique calling, or even sort of a calling, the more power to you. But if you view your place in the world as a series of ladders in place and income, it's sad.

As long as we have a philosophy that career="personal fulfillment" and that equates with Career Uber Alles, we're going to be in trouble in every imaginable way. This doesn't mean that what a person does for a living doesn't matter, but other things matter more, and if a person puts their career above everything else, in the end, they're likely to be unhappy and they're additionally likely to make everyone else unhappy. This may seem to cut against what I noted in the post on life work balance the other day, but it really doesn't, it's part of the same thing.

Indeed, just he other day my very senior partner came in my office and was asking about members of my family who live around here. Quite a few live right here in the town, more live here in the state, and those who have left have often stayed in the region. The few that have moved a long ways away have retained close connection, but formed new stable ones, long term, in their new communities. He noted that; "this is our home". That says a lot.

Get out there.

The ills of careerism.

Careerism, the concept that the end all be all of a person's existence is their career, has been around for a long time, but as the majority demographic has moved from farming and labor to white collar and service jobs, it's become much worse. At some point, and I'd say some point post 1945, the concept of "career" became incredibly dominant. In the 1970s, when feminism was in high swing, it received an additional massive boost as women were sold on careerism.

How people view their work is a somewhat difficult topic to address in part because everyone views their work as they view it. And not all demographics in a society view work the same way. But there is sort of a majority society wide view that predominates.

In our society, and for a very long time, there's been a very strong societal model which holds that the key to self worth is a career. Students, starting at the junior high level, are taught that in order to be happy in the future they need to go to a "good university" so they can obtain an education which leads to "a high paying career". For decades the classic careers were "doctor and lawyer", and you still hear some of that, but the bloom may be off the rose a bit with the career of lawyer, frankly, in which case it's really retuning to its American historical norm.

Anyhow, this had driven a section of the American demographic towards a view that economics and careers matter more than anything else. More than family, more than location, more than anything. People leave their homes upon graduating from high school to pursue that brass ring in education. They go on to graduate schools from there, and then they engage in a lifetime of slow nomadic behavior, dumping town after town for their career, and in the process certainly dumping their friends in those towns, and quite often their family at home or even their immediate families.

The payoff for that is money, but that's it. Nothing else.

The downside is that these careerist nomads abandon a close connection with anything else. They aren't close to the localities of their birth, they aren't close to a state they call "home" and they grow distant from the people they were once closest too.

What's that have to do with this topic?

Well, quite a lot.

People who do not know, in the strongest sense of that word know, anyone or anyplace come to be internal exiles, and that's not good. Having no close connection to anyone place they become only concerned with the economic advantage that place holds for them. When they move into a place they can often be downright destructive at that, seeking the newest and the biggest in keeping with their career status, which often times was agricultural or wild land just recently. And not being in anyone place long enough to know it, they never get out into it.

That's not all of course. Vagabonds without attachment, they severe themselves from the human connection that forms part of our instinctual sense of place. We were meant to be part of a community, and those who have lived a long time in a place know that they'll be incorporated into that community even against their expressed desires. In a stable society, money matters, but so does community and relationship. For those with no real community, only money ends up mattering.

There's something really sad about this entire situation, and its easy to observe. There are now at least two entire generations of careerist who have gone through their lives this way, retiring in the end in a "retirement community" that's also new to them. At that stage, they often seek to rebuild lives connected to the community they are then in, but what sort of community is that? One probably made up of people their own age and much like themselves. Not really a good situation.

Now, am I saying don't have a career? No, I'm not. But I am saying that the argument that you need to base your career decisions on what society deems to be a "good job" with a "good income" is basing it on a pretty thin argument. At the end of the day, you remain that Cro Magnon really, whose sense of place and well being weren't based on money, but on nature and a place in the tribe. Deep down, that's really still who you are. If you sense a unique calling, or even sort of a calling, the more power to you. But if you view your place in the world as a series of ladders in place and income, it's sad.

As long as we have a philosophy that career="personal fulfillment" and that equates with Career Uber Alles, we're going to be in trouble in every imaginable way. This doesn't mean that what a person does for a living doesn't matter, but other things matter more, and if a person puts their career above everything else, in the end, they're likely to be unhappy and they're additionally likely to make everyone else unhappy. This may seem to cut against what I noted in the post on life work balance the other day, but it really doesn't, it's part of the same thing.

Indeed, just he other day my very senior partner came in my office and was asking about members of my family who live around here. Quite a few live right here in the town, more live here in the state, and those who have left have often stayed in the region. The few that have moved a long ways away have retained close connection, but formed new stable ones, long term, in their new communities. He noted that; "this is our home". That says a lot.

Get out there.

Public (Federal) fishing landing in Natrona County, Wyoming. When we hear of our local politicians wanting to "take back" the Federal lands, those of us who get out imagine things like this decreasing considerably in number. We shouldn't let that happen, and beyond that, we should avail ourselves of these sites.

And our nature is to get out there in the dirt.

Go hunting, go fishing, go hiking or go mountain bike riding. Whatever you excuse is for staying in your artificial walls, get over it and get out.

Go hunting, go fishing, go hiking or go mountain bike riding. Whatever you excuse is for staying in your artificial walls, get over it and get out.

That means, fwiw, that we also have to quit taking snark shots at others in the dirt, if we do it. That's part of human nature as well, and humans are very bad about it. I've seen flyfishermen be snots to bait fisherman (you guys are all just fisherman, angler dudes and dudessses, and knock off the goofy crap about catching and releasing everything.. . you catch fish as we like to catch fish because nature endowed us with the concept that fish are tasty). Some fisherman will take shots at hunters; "I don't hunt, . . . but I fish (i.e., fishing hunting. Some "non consumptive (i.e., consumptive in another manner) outdoors types take shots at hunters and fisherman; "I don't hunt, but I ride a mountain bike (that's made of mined stuffed and shipped in a means that killed wildlife just the same)".

If you haven't tried something, try it, and the more elemental the better. If you like hiking in the sticks, keep in mind that the reason people like to do that has to do with their elemental natures. Try an armed hike with a shotgun some time and see if bird hunting might be your thing, or not. Give it a try. And so on.

Get elemental

At the end of they day, you are still a hunter-gatherer, you just are being imprisoned in an artificial environment. So get back to it. Try hunting. Try fishing. Raise a garden.

Unless economics dictate it, there's no good, even justifiable, reason that you aren't providing some of your own food directly. Go kill it or raise it in your dirt.

Indeed, a huge percentage of Americans have a small plot, sometimes as big as those used by subsistence farmers in the third world, which is used for nothing other than growing a completely worthless crop of grass. Fertilizer and water are wasted on ground that could at least in part be used to grow an eatable crop. I'm not saying your entire lawn needs to be a truck farm, but you could grow something. And if you are just going to hang around in the city, you probably should.

The Land Ethic

Decades ago writer Aldo Leopold wrote in his classic A Sand Country Almanac about the land ethic. Leopold is seemingly remembered today by some as sort of a Proto Granola, but he wasn't. He was a hunter and a wildlife agent who was struck by what he saw and wrote accordingly. Beyond that, he lived what he wrote.

A person can Google (or Yahoo, or whatever) Leopold and the the "land ethic" and get his original writings on the topic. I"m not going to try to post them there, as the book was published posthumously in 1949, quite some years back. Because it wasn't published until 49, it had obviously been written some time prior to that. Because of the content of the book, and everything that has happened since, it's too easy therefore to get a sort of Granola or Hippy like view of the text, when in fact all of that sort of thing came after Leopold's untimely death at age 61. It'd be easy to boil Leopold's writings down to one proposition, that being what's good for the land is good for everything and everyone, and perhaps that wouldn't be taking it too far.

If I've summarized it correctly, and I don't think I'm too far off, we have to take into consideration further that at the time Leopold was writing the country wasn't nearly as densely populated as it is now, but balanced against that is that the country, in no small part due to World War Two, was urbanizing rapidly and there was a legacy of bad farming practices that got rolling, really, in about 1914 and which came home to roost during the Dust Bowl. In some ways things have improved a lot since Leopold's day, but one thing that hasn't is that in his time the majority of Americans weren't really all that far removed from an agricultural past. Now, that's very much not the case. I suspect, further, in Leopold's day depression, and other social ills due to remoteness from nature weren't nearly as big of problem. Indeed, if I had to guess, I'd guess that the single biggest problem of that type was the result of World War Two, followed by the Great Depression, followed by World War One.

Anyhow, what Leopold warned us about is even a bigger problem now, however. Not that the wildness of land is not appreciated. Indeed, it is likely appreciated more now than it was then. But rather we need to be careful about preserving all sorts of rural land, which we are seemingly not doing a terrible good job at. The more urbanized we make our world, the less we have a world that's a natural habitat for ourselves, and city parks don't change that. Some thought about what we're doing is likely in order. As part of that, quite frankly, some acceptance on restrictions on where and how much you can build comes in with it. That will make some people unhappy, no doubt, but the long term is more important than the short term.

It's not inevitable.

The only reason that our current pattern of living has to continue this way is solely because most people will it to do so. And if that's bad for us, we shouldn't.

There's nothing inevitable about a Walmart parking lot replacing a pasture. Shoot, there's nothing that says a Walmart can't be torn down and turned into a farm. We don't do these things, or allow them to happen, as we're completely sold on the concept that the shareholders in Walmart matter more than our local concerns, or we have so adopted the chamber of commerce type attitude that's what's good for business is good for everyone, that we don't. Baloney. We don't exist for business, it exists for us.

If you haven't tried something, try it, and the more elemental the better. If you like hiking in the sticks, keep in mind that the reason people like to do that has to do with their elemental natures. Try an armed hike with a shotgun some time and see if bird hunting might be your thing, or not. Give it a try. And so on.

Get elemental

At the end of they day, you are still a hunter-gatherer, you just are being imprisoned in an artificial environment. So get back to it. Try hunting. Try fishing. Raise a garden.

Unless economics dictate it, there's no good, even justifiable, reason that you aren't providing some of your own food directly. Go kill it or raise it in your dirt.

Indeed, a huge percentage of Americans have a small plot, sometimes as big as those used by subsistence farmers in the third world, which is used for nothing other than growing a completely worthless crop of grass. Fertilizer and water are wasted on ground that could at least in part be used to grow an eatable crop. I'm not saying your entire lawn needs to be a truck farm, but you could grow something. And if you are just going to hang around in the city, you probably should.

The Land Ethic

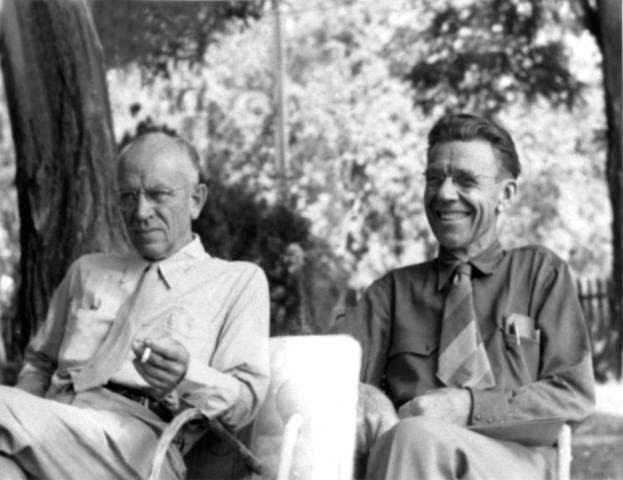

Aldo Leopold and Olaus Murie. The Muries lived in Wyoming and have a very close connection with Teton County, although probably the majority of Wyomingites do not realize that. This photo was taken at a meeting of The Wilderness Society in 1946. While probably not widely known now, this era saw the beginnings of a lot of conservation organizations. At this point in time, Leopold was a professor at the University of Wisconsin.

A person can Google (or Yahoo, or whatever) Leopold and the the "land ethic" and get his original writings on the topic. I"m not going to try to post them there, as the book was published posthumously in 1949, quite some years back. Because it wasn't published until 49, it had obviously been written some time prior to that. Because of the content of the book, and everything that has happened since, it's too easy therefore to get a sort of Granola or Hippy like view of the text, when in fact all of that sort of thing came after Leopold's untimely death at age 61. It'd be easy to boil Leopold's writings down to one proposition, that being what's good for the land is good for everything and everyone, and perhaps that wouldn't be taking it too far.

If I've summarized it correctly, and I don't think I'm too far off, we have to take into consideration further that at the time Leopold was writing the country wasn't nearly as densely populated as it is now, but balanced against that is that the country, in no small part due to World War Two, was urbanizing rapidly and there was a legacy of bad farming practices that got rolling, really, in about 1914 and which came home to roost during the Dust Bowl. In some ways things have improved a lot since Leopold's day, but one thing that hasn't is that in his time the majority of Americans weren't really all that far removed from an agricultural past. Now, that's very much not the case. I suspect, further, in Leopold's day depression, and other social ills due to remoteness from nature weren't nearly as big of problem. Indeed, if I had to guess, I'd guess that the single biggest problem of that type was the result of World War Two, followed by the Great Depression, followed by World War One.

Anyhow, what Leopold warned us about is even a bigger problem now, however. Not that the wildness of land is not appreciated. Indeed, it is likely appreciated more now than it was then. But rather we need to be careful about preserving all sorts of rural land, which we are seemingly not doing a terrible good job at. The more urbanized we make our world, the less we have a world that's a natural habitat for ourselves, and city parks don't change that. Some thought about what we're doing is likely in order. As part of that, quite frankly, some acceptance on restrictions on where and how much you can build comes in with it. That will make some people unhappy, no doubt, but the long term is more important than the short term.

It's not inevitable.

The only reason that our current pattern of living has to continue this way is solely because most people will it to do so. And if that's bad for us, we shouldn't.

There's nothing inevitable about a Walmart parking lot replacing a pasture. Shoot, there's nothing that says a Walmart can't be torn down and turned into a farm. We don't do these things, or allow them to happen, as we're completely sold on the concept that the shareholders in Walmart matter more than our local concerns, or we have so adopted the chamber of commerce type attitude that's what's good for business is good for everyone, that we don't. Baloney. We don't exist for business, it exists for us.

Some thought beyond the acceptance of platitudes is necessary in the realm of economics, which is in some ways what we're discussing with this topic. Americans of our current age are so accepting of our current economic model that we excuse deficiencies in it as inevitable, and we tend to shout down any suggestion that anything be done, no matter how mild, as "socialism".

The irony of that is that our economic model is corporatist, not really capitalist, in nature. And a corporatist model requires governmental action to exist. The confusion that exists which suggests that any government action is "socialism" would mean that our current economic system is socialist, which of course would be absurd. Real socialism is when the government owns the means of production. Social Democracy, another thing that people sometimes mean when they discuss "socialism" also features government interaction and intervention in people's affairs, and that's not what we're suggesting here either.

Rather, I guess what we're discussing here is small scale distributism, the name of which scares people fright from the onset as "distribute", in our social discourse, really refers to something that's a feature of "social democracy" and which is an offshoot of socialism. That's not what we're referencing here at all, but rather the system that is aimed at capitalism with a subsidiarity angle. I.e., a capitalist system that's actually more capitalistic than our corporatist model, as it discourages government participation through the weighting of the economy towards corporations.

The irony of that is that our economic model is corporatist, not really capitalist, in nature. And a corporatist model requires governmental action to exist. The confusion that exists which suggests that any government action is "socialism" would mean that our current economic system is socialist, which of course would be absurd. Real socialism is when the government owns the means of production. Social Democracy, another thing that people sometimes mean when they discuss "socialism" also features government interaction and intervention in people's affairs, and that's not what we're suggesting here either.

Rather, I guess what we're discussing here is small scale distributism, the name of which scares people fright from the onset as "distribute", in our social discourse, really refers to something that's a feature of "social democracy" and which is an offshoot of socialism. That's not what we're referencing here at all, but rather the system that is aimed at capitalism with a subsidiarity angle. I.e., a capitalist system that's actually more capitalistic than our corporatist model, as it discourages government participation through the weighting of the economy towards corporations.

It's not impossible

Now, I know that some will read this and think that it's all impossible for where they are, but truth be known it's more possible in some ways now than it has been for city dwellers, save for those with means, for many years. Certainly in the densely packed tenements of the early 19th Century getting out to look at anything at all was pretty darned difficult.

Most cities now at least incorporate some green space. A river walk, etc. And most have some opportunities for things that at least replicate real outdoor sports, and I mean the real outdoor activities, not things like sitting around in a big stadium watching a big team. That's not an outdoor activity but a different type of activity (that I'm not criticizing). We owe it to ourselves.

Now, clearly, some of what is suggested here is short term, and some long. And this is undoubtedly the most radical post I've ever posted here. It won't apply equally to everyone. The more means a person has, if they're a city dweller, the easier for it is for them to get out. And the more destructive they can be when doing so, as an irony of the active person with means is that the mere presence of their wealth in an activity starts to make it less possible for everyone else. But for most of us we can get out some at least, and should.

I'm not suggesting here that people should abandon their jobs in the cities and move into a commune. Indeed, I wouldn't suggest that as that doesn't square with what I"m actually addressing here at all. But I am suggesting that we ought to think about what we're going, and it doesn't appear we are. We just charge on as if everything must work out this way, which is choosing to let events choose for us, or perhaps letting the few choose for the many. Part of that may be rethinkiing the way we think about careers. We all know it, but at the end of the day having made yourself rich by way of that nomadic career won't add significantly, if at all, to your lifespan and you'll go on to your eternal reward the same as everyone else, and sooner or later will be part of the collective forgotten mass. Having been a "success" at business will not buy you a second life to enjoy.

None of this is to say that if you have chosen that high dollar career and love it, that you are wrong. Nor is this to say that you must become a Granola. But, given the degree to which we seem to have a modern society we don't quite fit, perhaps we ought to start trying to fit a bit more into who we are, if we have the get up and go to do it, and perhaps we ought to consider that a bit more in our overall societal plans, assuming that there even are any.

No comments:

Post a Comment